Freedom’s Edge, a Poem

By Yerusalem Work

You stood castle-high, singing on the midnight-moonlit balcony

Your voice reached across the vast, star-scattered skies

Tears poured from my eyes

You left a palace to address the issue of contentment

You gave us light—a messenger of the messengers

My thoughts took flight

The height of a hummingbird, the rhythm complete with hope inside me

You elevate me

I face you and my soul smiles,

the kiss of peace greeting you with solemnity

In a labyrinth of faith-filled promises,

I push against the walls of fear and regret.

I travel with poetry as my guide.

You illuminate the day and night

with your heart’s meditation

The fire you put in me makes me rise to my feet–

I see shadows repeat in a cave of my doing,

but nothing can compare to your presence

Only now can I breathe

with depth and freedom,

only now do I discover the unveiling of life, the mystery of being

Through love,

I become human

Through prayer,

I experience divine union and

the absence of time.

You, the cliff’s edge, are sublime.

You, a decorated hero, are the friend I find by the riverside.

Dipping in our consciousness…never the same feeling twice.

Happiness. Lovingkindness.

Splashing in knowledge, refreshing, an awakening,

I ask you to dream with me and carry me with you through our journey.

I am a butterfly alight on your shoulder.

Graceful movement. Grateful conclusions.

Reading into you. I believe in forgotten truths.

I pray the Lord heals me and you.

After terrible loss,

having a hand to hold is proof of God’s mercy.

I am on my knees and only He can hear me.

Who truly knows me?

To hear the author read this poem, please visit: https://www.facebook.com/100004823402356/posts

Yerusalem Work, a creative writer and the membership director of the Congregational Library Association, has a heart for interfaith dialogue and is a passionate community builder. A holder of a master’s degree in library science and prolific author, she regularly blogs and self-publishes her writing. Her short stories and poetry have been published in Muslim Matters and Tysons Interfaith. She considers it an honor and a pleasure to write on Islamic themes.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

More than anything else, spirituality is a quest to find one’s authentic self, to review and interpret life events and develop a sense of personal integrity; and it should not be confused with religion, which remains nevertheless an important path for many.

That was the consensus of a February 4 webinar presented by the Rev. Dr. Al Fuertes of George Mason University’s School of Integrative Studies, which joined Tysons Interfaith to explore the connection between spirituality and well-being. Most heartening was Dr. Fuertes’s report that his students and nearly two-thirds of college students polled nationwide long to discuss things that matter to them on the personal level, things that are meaningful and purposeful and in which they can find beauty and meaning.

People who successfully perform this kind of soul-searching and synthesis develop the best potential to perceive and enjoy a good quality of life. Such meaning-making involves being mindful about our emotions, thoughts, and surroundings, a kind of mindfulness that many researchers and practitioners also recommend for achieving good health outcomes, like stress reduction.

Although well-being is not just the absence of disease or illness but a complex combination of a physical, mental, emotional, and social factors, once we are able to find our authentic vocation, our true self, or what some call our “sacred face,” we can achieve a sense of purpose that has been linked to a lower risk of mortality. Other studies have found out that prayer or healing ceremonies can have positive outcomes on alleviating symptoms and improving quality of life. And, arguably, achieving this kind of personal well-being can help bring peace to the broader community.

We hope to explore more of these applied approaches to spirituality in future Oneness of Humanity programs. Please join us.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Lois Herr, First Church of Christ, Scientist, McLean

On February 4, 2024, Tysons Interfaith will partner with George Mason University for an Webinar entitled Spirituality and Well-Being: Exploring the Connection. As we prepare for this engaging and interactive event, I wanted to share a recent article from the Christian Science Monitor, that is completely relevant to our upcoming discussion. It is entitled: “The glue of seeing good.”

I hope many people will be interested in joining our February 4 webinar, and/or may be encouraged by the findings of this article:

“The glue of seeing good”

Surveys show a breadth of spirituality binding Americans to each other in connections of empathy and affection.

The Christian Science Monitor: December 21, 2023

Worried that Americans are marching into an election year more divided than ever? Take another look.

In October, a first-ever Connection Index offered a striking counternarrative. Conducted by The Harris Poll, it found that 76% of Americans see the good in those they disagree with and 71% have friends who hold views they don’t share.

Those attitudes may reflect something more than mere personal affection. A new survey of American spirituality reveals a deeper basis of thought binding society together. Published by the Pew Research Center this month, the study asked more than 11,000 Americans how they thought about spirituality. It found a recurring theme of connectedness.

For example, 74% described “being connected with something bigger than myself” as an essential quality of spirituality. Seventy percent said the same about “being connected with God,” while 64% said “being connected with my ‘true self’” and 54% said “being open-minded” were essential to spirituality. Nearly 4 in 10 said spirituality involved “being connected with other people.”

Overall, the survey found, 9 in 10 Americans believe in God or a power higher than themselves, 70% describe themselves as spiritual, and 53% expressed a “deep sense of connection with humanity.” These views were drawn from across multiple demographic and denominational boundaries.

For years, medical practitioners have been gathering evidence that spirituality is a vital factor in health. Some 90% of medical schools in the United States, 59% in Britain, and 52% in German-speaking countries now include spiritual studies in their curricula. As the Pew study notes, society is drawing new distinctions between being spiritual and being religious. Doctors and nurses incorporating spirituality in health care often start with the simple act of listening.

“When I think of spirituality in health care, it’s the connection we make with other people,” Diana Vereni, an associate professor of physical therapy at Sacred Heart University in Connecticut, told a public forum in July. Such empathy and compassion promote healing by alleviating fear and affirming a sense of individual worth, medical studies have shown.

They have a similar effect on society as a whole. “Social connectedness influences our minds, bodies, and behaviors – all of which influence our health and life expectancy,” the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded in a March study. “Inclusive connections in our neighborhoods, schools, places of worship, workplaces, and other settings are associated with … and support the overall well-being, health, safety, and resilience of communities.”

For one respondent in the Pew study, spirituality meant being able to “see the beauty in everything, feel the love of Mother Nature, to know that there is something out there that is greater than me, that loves me, that looks out for me.” That kind of seeing good may be the reason behind the Connection Index finding that Americans don’t need to agree in order to get along.”

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Over the last few weeks, these words have become my daily prayer: “Let there be peace on earth.” With the war in Ukraine entering its twenty-first month and the war in Israel and Gaza expected to continue into the new year, the loss of lives and the displacement of people have been overwhelming. In places like Myanmar and Sudan there is constant civil unrest that affects the innocent. Conflict has become the norm rather than the exception even in our own country. And yet it is in our current context that Christians enter the Advent season (December 3 through December 24) to prepare ourselves not only for the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ but for his Second Coming.

Advent comes with four major themes to meditate upon – peace, hope, joy, and love. This is a reflection on peace.

For those of us who are older (smile), the title of this article should sound familiar. It comes from a well-known Christmas song that was written in 1955 by Jill Jackson-Miller. She wrote the lyrics and her husband, Sy Miller, wrote the melody.

Let there be peace on earth, and let it begin with me.

Let there be peace on earth, the peace that was meant to be.

With God, our creator, family are we. Let us walk with each other in perfect harmony.

The song was introduced at a retreat center in California for a group of young people who were from a wide variety of religious, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. They were there for a week-long experience to develop friendships with people who held different views from their own. They attended educational seminars that enabled them to learn the skills they needed to have open and healthy discussions on difficult topics. By the end of the week, it was the hope that they would be able to work together. It is in this setting that this song was introduced. It turned out to be a perfect ending to an amazing week. Once the young people learned the lyrics, they got up, locked arms, formed a circle, and faced each other as they sang this song of peace. It is a simple song with a powerful message that has been recorded and translated and sung all over the world.

In the Old Testament, the word for peace is shalom which is derived from a root word that means wholeness or completeness. In the Bible, it has less to do with the absence of war and conflict and has more to do with our overall well-being. When someone says they are at peace, they are letting us know that they are content even when in the middle of a hardship or struggle. They know (truly know) that God is with them. It has the same connotation in the New Testament. Jesus expresses the idea that peace comes from peacemakers and true peacemakers are characterized by their poverty of spirit, their ability to mourn for their broken world, and for their hunger for healing and reconciliation.

Too often we restrict our thoughts about peace as simply the end of conflicts. Certainly, an end to violence is something that we should pray for in Ukraine, the Middle East, in our community, and even in our homes. But it seems like the peace that is talked about in Scripture is more than the absence of something negative. It has its own presence and energy. It is a gift from God that occurs when we turn over to God a certain amount of control of all the things that we worry about. We do not surrender responsibility, but we recognize limits as to what we can affect or achieve on our own. And once we acknowledge our limits, we place ourselves and others in the hands of God. And God’s response is to give us peace, a peace that allows us to look up and see the gifts around us and not just the troubles that consume us.

People of good will long for peace. But our human experience tells us that peace on earth is elusive. In contrast, the peace of God comes to us as pure gift through God’s grace alone. We release our grip on all the things that we are trying to hold together on our own, and in return God gives us a sense of well-being that can only come from God.

During this Advent season, I will continue to pray, “Let There Be Peace on Earth.” Peace among the people of the earth and peace in our hearts as we entrust the burdens of this world to our creator.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

On Thursday, December 7th at sundown, Jews all over the world will begin the celebration of the eight-day festival of Chanukah with the lighting of the first candle on the menorah. The celebration this year will not be the same, as war rages in Israel and Gaza and its repercussions are felt around the world, including of course in our communities.

What is very important to remember in a time of watching the rise of antisemitism all over the world, with a 388% increase in incidents in the United States since October 7th over the same time period last year, is that this holiday celebrates the victory of religious freedom – a cause, unfortunately, still being fought for by millions of people the world over. We must note that Jews are not alone, there has also been a significant increase in anti-Muslim hate incidents.

We are living in very dark times. Wars and hatred spread across the face of the earth, and many in the name of religion. As we begin this holiday season, with many religions celebrating, let us not forget the world is large; there is room for everyone to worship as they choose and not live in fear.

Perhaps we can use the light of this holiday to ask for the wellbeing and safety of all people, regardless to whom they address their prayers.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

The International Day of Peace was established in 1981 by the United Nations General Assembly. Two decades later, in 2001, the General Assembly unanimously voted to designate September 21st as its annual commemoration – a 24-hour period of non-violence and cease-fire for groups in active combat.

Through the years it has been realized that “active combat” is not limited to war zones. Active combat is experienced in cities and country sides aroused by fear, avarice, racism and other prejudices, politics, and contrasting ideologies.

The origin of the World Day of Peace can be traced back to 1967 when Pope Paul VI established it as a feast day of the Catholic Church. It was designated as a day of universal peace devoted to commemorating and strengthening the ideals of peace both within and among all nations and peoples. It has come to be a time to actualize those ideals – to promote and maintain peace.

The United Nations also celebrates the International Day of Living Together in Peace, annually on May 16th, to stir individuals to mobilize efforts within the international community to promote peace, tolerance, inclusion, understanding and solidarity.

Imagine people of all nations, cultures, religions, and backgrounds working side by side in harmony. The power of imagination has been the root of social change throughout the ages, however, if left solely in the imaginal realm, nothing happens. Change happens when our imagination inspires us to action – action that is uniquely our own – action that uproots us from our complacency and calls us each to use our Divinely imbued skills and abilities to support our world in rising out of violence into peace.

Some people who describe themselves as peace advocates have difficulty wrapping around the notion that they can be both a powerful presence for peace and be an activist. Jesus was a Love activist: He came to teach love, and He was an unwavering stand for what he believed.

An activist is merely someone who is willing to stand by and for his/her values and beliefs. It is a willingness to engage on behalf of something that matters – equity, environment, health, welfare, education, to name just a few. Often that stand is taken vigorously, perhaps emphatically, and is the out-picturing of a passionate desire to do good. It can be extremely empowering.

Spiritual activism engages the power of spiritual consciousness and groundedness to guide individual actions. Spiritual activism takes myriad forms ranging from contemplative prayer to marching and picketing. How we each display our activism is as varied as humanity. Our shared common goal is to effect change based on spiritual principles and values. The outward expression of our activism emerges from our inner work. Peace activists, generally, lean toward pacifism, choosing nonviolent methods to prevent or end violent conflicts, to end non-democratic rule, and to dissolve prejudices such as racism, homophobia, and gender biases. Spiritual activists, many of whom are Peace activists, use peaceful means to achieve change. I am both. We express our views clearly, but succinctly and at a volume that doesn’t have others reaching for ear plugs. We avoid winding ourselves into a frenzy over things we can’t control. Instead, we draw on inner strength and guidance using attributes such as our belief in the Oneness of all creation, Love as a universal principle, compassion and reciprocity, simplicity and optimism, harmony and humility, responsibility, and accountability. We set the intention to be kind and considerate and refrain from criticizing others. We join together to make the world a better place. We are drawn to like-minded people wherever we are and connect spontaneously.

The question arises, why should I be an activist? Activism seeks to influence social and political outcomes by mobilizing citizens to take actions that generate widespread or well-targeted public attention around specific issues.

The United Nations International Day of Peace and their International Day of Living Together in Peace are occasions in which Peace activists around the globe present public dialogues, peace meditations and vigils, and an array of educational offerings to heighten awareness and support of Peace. Each of these is a form of “Peace Demonstration.” We draw attention to the need to heal our planet and grow strong peaceful communities.

The actions we take are demonstrations of Spirit’s call within us to do our part to manifest a world that works for everyone. Each of us has an inborn desire to experience peace. We sense the call to remove all obstacles to the free flow of peace and love. We respond affirmatively to opportunities to become radiantly contagious purveyors of peace, connecting with individuals, bringing them together in small groups that grow into larger and larger groups of individuals dedicated to peace – the essential foundation of a world that works for all.

Our efforts cannot be haphazard – we need to abide in and as peace moment by moment.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the United Nations General Assembly declaration “International Day of Peace.” Its purpose remains strong and essential to the wellbeing of our planet and all its inhabitants. Life is better in a world at peace.

Regardless of where we come from or what languages we speak, we are more alike than we are different. Honoring our commonalities makes peace possible. We draw on the wisdom and experience of the peacemakers and peacekeepers to learn how we can individually and collectively be catalysts for peace – how we can manifest a world that works for everyone, everywhere.

Violence is common in nations and communities that struggle with poverty, disease, and limited access to education and healthcare. Until we are willing to soften our own perspectives so we can catch a glimpse of someone else’s experience, peace will remain beyond our reach.

Peace is possible. We have the opportunity to transform the world so that our loved ones can live in sustainable peace. We are called to step outside our comfort zones – to become Peace Advocates. The impact of each small act is immense.

Join me again in the imaginal realm: Envision and feel how different life would be if we all were simply kind and respectful of one another. We can all contribute to the worldwide culture of peace through generosity of spirit, prayer, advocacy, education and ensuring access to clean water and health resources. Every small effort makes a difference.

Today, more than any other time in history, peace relies on the commitment to not only achieve equality, but to secure equity for all persons – to fulfill our vision of a world that works for everyone, everywhere.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

On Saturday, June 17, Historic Pleasant Grove Church, an historic site and museum, held their annual Spring Fair and Open House. Pleasant Grove is located at 8641 Lewinsville Road, McLean, Virginia 22102, just on the outskirts of Tysons.

As described on their website: “Historic Pleasant Grove is a community landmark in McLean, Virginia built by and for African and Native Americans in the late 19th century. No longer an active church, the simple-yet-striking Carpenter Gothic structure is an historic site managed by the Friends of Pleasant Grove, who foster diversity through free cultural events throughout the year, operate the on-site museum, and rent the space.”

Some of Pleasant Grove’s founding families’ members are buried on the property, including members of the Sharper family. On the day of the open house, I took time to really appreciate the Carpenter Gothic Architecture and craftmanship of Lewis Henry Sharper, the master carpenter who led much of the work on the building. I also learned that among Pleasant Grove’s founding families were members of the Pamunkey Native American Tribe, including John Mills who also helped build the structure.

My husband, Tyler, and I (and our dog Scrappy) were also pleased to speak with Michelle Arcari, Board President of the Friends of Pleasant Grove. We learned about the history of the organization, their on-going work to preserve the structure and the history of the community, as well as their efforts to promote cultural diversity through events held throughout the year.

Pictured: Tyler Posey, Michelle Arcari and Scrappy Posey

To learn more about this historic gem in our midst and upcoming events public events planned at the site, I encourage you to visit Historic Pleasant Grove’s website at historicpleasantgrove.org/.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

An article I read from the Stanford Center for Longevity notes that there is a relationship between volunteering and improved physical health and cognitive function. “Research also shows that volunteers report elevated mood and less depression, and that volunteers report increased social interactions and social support, better relationship quality, and decreased loneliness.” longevity.stanford.edu A contributor to Deseret News had this to say about her volunteer experience: “I’ve experienced the boost in happiness, the sense that I was part of something bigger. I made friends, formed connections that I still have to this day, and I felt more optimistic about the world when I was surrounded by people who, like me, were trying to help others.” deseret.com/coronavirus/2022/4/17.

Of course, volunteering strengthens communities as well. As people of different backgrounds come together to serve our neighbors, we discover that we have much more in common than we ever imagined. Whether it is donating our time, talents or resources, each selfless act truly does help make the world a better place.

Want to learn more about some of the non-profits doing phenomenal work in the Tysons area? Spring and summer 2023, Tysons Interfaith will present a series of blog posts highlighting local organizations that are working to improve the lives of our neighbors. Please look for these periodic posts, or feel free to visit the Tysons Interfaith Resources Page for a comprehensive list of non-profit organizations in our area: tysonsinterfaith.org/resources.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

What is your “worldview”? What do you hold dear? The answers to these questions are both the composite and the creator of your attitudes, values, stories, and expectations about your world and the world around you. They inform your every thought and action. Your worldview manifests as your ethics, religion, philosophy, and beliefs.

We arise from our cultures of origin, so we are a product of that culture, and we have everything that is necessary to be the producers of new cultures. Humans have been creating cultures since we first walked the earth.

Are you a “glass-half-full” person – an optimist that sees the positive in everything, or a “glass-half-empty” pessimist that goes to the darker side, thinking the worst of any situation? Most of us vacillate between the two depending on context.

If you had magical powers (which, of course, you do), what culture would you create? Would it be utopian? Would everyone get along without challenges or disagreements? Would it be so peaceful that terminal stasis might set in? Or would it be a world in which citizens are truly free to think independently, to share the breadth of their creativity, to debate respectfully, challenge other’s opinions without fear, collectively focusing on solutions and constructive evolution? Could a world of health, harmony, and unconditional high regard that supports everyone in living their best yet to be, prevail?

Thousands of people gathering in small groups are responding to the heart-call to create a world that works. In the interfaith world, we are creating a culture of connection that begins with compassionate curiosity. We are concerned about others’ experiences and encourage everyone to learn with and from one another. Kindness, stemming from mutual respect, is blossoming. Curiosity, which plays a huge role in how we relate to our world, is the strong desire to learn something more, something new. Our willingness to reach beyond the culture in which we were raised depends on our internal sense of safety blended with the divine urge to experience the unknown. Our culture of origin instilled acceptable and customary beliefs and social forms and formulas in us. We unconsciously embraced the material traits of our racial, religious and social groups. This worldview has out-pictured as our everyday existence – our way of life and the people with whom we share our lives. It is how we relate to all creation, our chosen diversions, the places we reside and our travels. As years have passed, some have stayed deeply linked to those original perspectives. Most of us have evolved, some more than others.

Some people look at the world and see it fractured, fragmented into myriad separate pieces. All they see are differences: different skin color, different size, shape, ethnicity, religion … different climates, different architecture. Different everything. Theirs is a world of “me and us” versus “other” – constantly contrasting what they believe to be known and safe with all that is different. The leap to an assumption that “different is dangerous” is all too easy. Gripped in fear, “fight, flight or freeze” instinctive, defensive reactions take over. Resourcefulness disappears.

Others, drawn by our common human desire to connect, may be challenged to find ways to relate to those individuals and groups that don’t align with our worldview. When confronted with personalities and appearances unlike ours, we may fumble and experience a jumble of emotions, yet continue to pursue connection. We experiment. Some of our tries turn out to be life-affirming and others quite opposite, and we don’t give up. We look around and note in awe and wonder, the myriad distinction of creation in expression. We drink in commonalities and celebrate all the differences. We recognize that we are looking at the same world through different subjective filters.

Commonalities prevail throughout nature. We are all made of the same stuff. For the most part, it is only when personality, rather than physicality, is brought into the equation that concerns about “different” crop up. Distinctions within commonalities are what make Life rich. Innate distinctions are what express as myriad appearances, gifts, talents, and desires.

The tension of opposites – the pull and push of life – stirs creativity. New solutions, new ways of being together are revealed. The Divine Urge within each of us desires to resolve conflict and harmonize our world. Coming together across myriad cultures and faith traditions, contemplating co-existence, I hear within me, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.” What if we were to ask, “What do we have in common? Let me count the ways.” I am sure we would discover ways to love one another. And, what if in love, we were to ask, “Tell me how it is to be you, your life, and those you love.”

Ernest Holmes shared what won’t work: “You cannot draw love into your consciousness through hate. You cannot draw peace from confusion. You cannot see beauty through ugliness, nor hear harmony while your ears are filled with discord.” So what will work?

We must develop a Culture of Connection! It may be easier than you think, here are some simple steps:

- Embrace your desire to create a Culture of Connection and commit to doing your part

- Set your intention to consistently be present in your conversations

- Silence our fear-mongering self-talk to the best of your ability

- Enter a consciousness of Love because it is contagious

- Express genuine, compassionate curiosity

- Initiate conversations – talk to strangers even though your mother told you not to.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

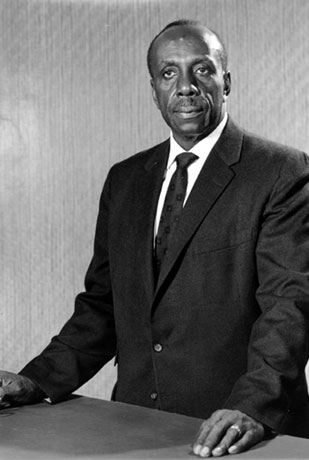

In recognition of Black History Month, I commend to you this prayer by Howard Thurman:

Lord, Lord, Open Unto Me

Open unto me, light for my darkness

Open unto me, courage for my fear

Open unto me, hope for my despair

Open unto me, peace for my turmoil

Open unto me, joy for my sorrow

Open unto me, strength for my weakness

Open unto me, wisdom for my confusion

Open unto me, forgiveness for my sins

Open unto me, tenderness for my toughness

Open unto me, love for my hates

Open unto me, Thy Self for myself

Lord, Lord, open unto me!

Thurman was born in 1899 and raised in the segregated South. He is recognized as one of the great spiritual leaders of the 20th century renowned for his reflections on humanity and our relationship with God. Thurman was a prolific author (writing at least 20 books); perhaps the most famous is Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), which deeply influenced Martin Luther King, Jr. and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. Thurman was the first black person to be a tenured Dean at a PWI (Boston U). He also cofounded the first interracially pastored, intercultural church in the US.

Source: https://www.xavier.edu/jesuitresource/online-resources/prayer-index/prayers-for-black-history-month1

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.