On a recent October Sunday, the Reverend Fran Gardner-Smith and people of St. Thomas Episcopal celebrated the Feast Day of Saint Francis of Assisi with an outdoor service attended by about 50 people and 11 dogs! Following this service, Rev Gardner-Smith shared the following communication with her congregation:

“Francis is known for his love of all creatures and for creation. At our outdoor service, we heard this reading from one of Francis’ sermons entitled “Peace, birds, peace!”:

‘My brother and sister birds, you should greatly praise your Creator and love him always. He gave you feathers to wear, and wings to fly, and whatever you need. God made you noble among his creatures and gave you a home in the purity of the air, so that, though you do not sow nor reap, he nevertheless protects and governs you without your least care.’

At the service, our choir sang one of my favorite choral pieces, “For the Beauty of the Earth” arranged by the English composer John Rutter. You can hear youth from the Milwaukee Vocal Arts Academy singing it here.

I hope you can find a small way to honor St. Francis today. Take a walk outside. Admire some leaves that are beginning to turn color as we move into October. Snuggle with an animal who shares your home. Whatever your day holds, may you find beauty. “

On that same October Sunday, across town at Redeemer Lutheran, Pastor Sandy Kessinger delivered a sermon also reflecting on this beautiful time of the year and on Psalm 8 that is excerpted here:

“O Lord, our Sovereign, how majestic is your name in all the earth! When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars that you have established; what are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?”

On this important topic Pastor Kessinger had this to say (summarized from her sermon, full text can be found here.):

“Who are we that God is so mindful of us? A better question is – Do we value ourselves as much as God values us? How quick we are to look at our faults and not see our gifts.

We need to look up at the heavens and the sky, the moon and the stars, the mountains, and the oceans, and place ourselves among the manifestation of God’s glory. God orders all things and gives us infinite value and worth in spite of ourselves.

Who are we? We are children of God, a little lower than the angels, and crowned with glory and honor. And in his infinite wisdom God also gave us partners so that we do not need to go it alone. May we live into what God intended for us when God created us in his image.”

As the trees begin to turn, I will reflect on Rev. Gardner-Smith and Pastor Kessinger’s messages. I will give thanks for the beauty of the earth, my sometimes silly and beloved animal companions, and the wonderful friends I have made through Tysons Interfaith – all members of the same human family, valued and partners in spiritual living.

.

My wife and I recently drove west, toward the Shenandoah mountains, to enjoy the beautiful early Autumn weather and the scenery.

On our return, we stopped at the parking lot of Trinity Episcopal Church in Upperville to stretch our legs and admire the architecture. Tacked on a wall near the church entrance was the following appeal to people of all faiths, as we collectively work through the pandemic:

- May we who are merely inconvenienced remember those whose lives are at stake.

- May we who have no risk factors remember those most vulnerable.

- May we who have the luxury of working from home remember those who must choose between preserving their health and paying their rent.

- May we who have the flexibility to care for our children when their schools close remember those children who will go hungry with no school meals.

- May we who have to cancel our trips remember those who have no place to go.

- May we who are losing our margin money in the tumult of the economic market remember those who have no margin at all.

- May we who settle in for quarantine at home remember those who have no home.

- As fear and divisiveness grip our country, let us choose love.

- During this time when we cannot physically wrap our arms around each other, let us find ways to become the loving embrace of God to our neighbor.

This community of faith is not exactly a poverty-stricken rural parish. I was therefore especially moved by the words on the slightly weathered sheet of paper reminding me to be mindful of the needs of others.

When things are not going well for me personally, I become upset with the world around me and complain – under my breath or to whoever will listen. The above phrases remind me, however, how fortunate I am. My personal “woes” are mostly self-centered and trivial in view of the realities faced daily by the women, men, and children alluded to above. I must not forget them in my haste to serve myself.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the United Nations General Assembly declaration “International Day of Peace.” The purpose of the International Day of Peace was and still remains, to strengthen the ideals of peace around the world.

In 2001, September 21st was set as the annual day of commemoration – not only as a time to discuss how to promote and maintain peace among all peoples but most remarkably, as an annual 24-hour period of global ceasefire and non-violence for groups in active combat. https://www.un.org/en/observances/international-day-peace

The International Day of Peace reminds us of our commonalities. Regardless of where we come from or what languages we speak, we are more alike than we are different. Honoring those commonalities makes peace possible. Life is better in a world where peace exists. We draw on the wisdom and experience of the peacemakers and peacekeepers to learn how we can individually and collectively be catalysts for peace – how we can manifest a world that works for everyone, everywhere. Nations and communities around the world struggle with poverty and disease, severely limited access to education and healthcare, particularly in areas where violence is common.

There is something here much bigger than our day-to-day routines. We have the opportunity to transform the world so that our loved ones can live in sustainable peace. To achieve this we are called to step outside our comfort zones. Until we are willing to soften our own perspectives so we can catch a glimpse of someone else’s experience, peace will remain beyond our reach.

Peace is possible. The impact of each small act is immense. Imagine: If we were all simply kind and respectful of one another, how different life would be. We can all contribute to the worldwide culture of peace through generosity of spirit, prayer, advocacy, education and ensuring access to clean water and health resources. Every small effort makes a difference.

Throughout history, dating back to the Peace of God (989 AD) and Truce of God (1027 AD) we see movements that arose from the desire to curb violence by limiting the days and times nobility could practice violence. Most societies have lived in peace most of the time. Today, we are much less likely to die in war than our parents or grandparents. Since the establishment of the United Nations and the creation of the Charter of the United Nations, governments are obligated not to use force against others unless they are acting in self-defense or have been authorized by the UN Security Council to proceed.

Centers for Spiritual Living selected United Nations International Day of Peace in 2016, to conduct a ceremony at the Home Office in Golden, Colorado, to dedicate a Peace Pole and to formally recognize the Collective Meditation for Peace Initiative as an integral and essential element of our organization. The Heart of Peace Initiative coordinates weekly online Collective Peace Meditations and numerous events throughout the year.

At a Centers for Spiritual Living event in 2016, Rev. Dr. Kenn Gordon reminded everyone that every day must be dedicated to peace – that the consciousness of humanity must be uplifted to abiding in and as peace moment by moment. As he said, a Peace Pole is a material replica of the intention that has brought it into form, just as the actions we take demonstrate Spirit’s call to do our part to manifest a world that works for everyone. World peace is a product of what is in the hearts of individuals. To achieve world peace, we must begin with the individual. In order for us to experience and express peace, we must first reveal that peace from within us – to remove all obstacles to the free flow of peace and love.

Religious Science has always been a powerful presence for peace, a core attribute of our philosophy of Oneness. As Dr. Ernest Holmes explained in Spiritual Awareness, “When we become conscious of our existence as an idea in the Mind of God, we shall find that we are walking in pathways of peace; that something within us acts like a magnet to attract that which belongs to itself. This something is Love, the supreme impulsion of the universe.”

Today more than any other time in history, peace relies on the commitment to not only achieve equality, but to secure equity for all persons – to fulfill our vision of a world that works for everyone, everywhere.

The Jewish High Holidays begin with the celebration of Rosh Hashanah the evening of Monday, September 6th and end with Yom Kippur at sundown Thursday, September 16th. The High Holidays are a time when many Jews make their strongest identification with Judaism, with their congregation, and with the Jewish people.

These ten days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are known as the “Days of Repentance.” The holidays are celebrated in accord with the lunar-solar cycle. Consequently, on the Gregorian calendar the dates move annually. You might hear Jews describe this year’s High Holidays as “early.”

Rosh Hashanah literally means in Hebrew, “the head of the year.” The Erev (Eve) Rosh Hashanah service Sunday evening sets the stage to welcome the Jewish new year of 5782. It is also when the “Book of Life” is opened and is left open during the days of repentance. Jews are encouraged to identify things they have done wrong, might have done better, and to express sorrow for them, expressing sorrow to those affected. Hence the name “the Days of Repentance.” At the dramatic concluding Yom Kippur service, the Book of Life is symbolically closed for another year.

In Reform Jewish Congregations, the Erev Rosh Hashanah service is following by a full day of worship, this year Tuesday, September 7th. In Conservative and Orthodox Jewish Congregations, there is an additional day of Rosh Hashanah observance on Wednesday, September 8th.

These services feature special prayers delivered in a special High Holiday “trope” or chants; melodies heard only this time of the year. The music is soaring, the prayers special, the sermons special, with much of the worship experience dating back centuries. The Rosh Hashanah services conclude with the blowing of the shofar, or ram’s horn. This signals that we have all come together as the Jewish people once more, it marks the beginning of a new year, and that this is the time to commit to doing better in the year ahead.

During this time Jews will set our plates of apples and honey, the apples representing our world and the honey the sweetness of the new year. This is also the only time of the year that one has round challahs rather that the traditional loaf for services and at home. Again, the round challah represents the globe and recognizes this time as the birthday of the world.

The days following this service and leading up to Yom Kippur are to be a period of introspection. It is to be a time for “teshuva,” or turning around, identifying how one can do better.

On Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement, these commitments are entered into the figurative Book of Life. From Erev Yom Kippur (Eve of Yom Kippur) through the next day the worship experience is solemn and serious. If one’s health allows, it is traditional that Jews fast from the start of the Erev Yom Kippur service through sunset of Yom Kippur service. The holiday concludes with a Break the Fast meal, often with family and friends.

For those who have fulfilled the mitzvah, or commandment, to observe these holidays, one leaves with a renewed sense of purpose, of commitment, and of peace.

The traditional greeting to Jews during this High Holiday period is to wish one another a happy new year. In Hebrew this is, “Le Sha-nah To-vah.” It means literally, “Happy New Year.” One can also say, “Yom Tov,” happy holiday, and on Yom Kippur, wish one an easy fast.

May this year’s Days of Repentance be a time of sincere renewal, commitment, and peace for all. “Le Shanah Tova!”

A recent survey of religion in America provides some granularity when it comes to the so-called decline in religiosity in these United States. Survey: White Mainline Protestants Outnumber White Evangelicals

The data show that contrary to other research, the percentage of Americans identifying with formal denominations is on a rebound from a low in 2018. Is this good news? Well, there’s a lot to be said for maintaining a skeptical attitude about formal religion. And yet, at the same time, this modest (re)turning to organized religion may be a response to the spiritual void that “mass society” represents.

Philosopher, and deeply agnostic, Hannah Arendt, summed up “mass society” thus:

All of the features, however, that mass psychology has by now identified as typical of man in mass society: his abandonment (Verlassenheit—and this abandonment is neither isolation nor solitude), along with his utmost adaptability; his irritability and lack of support; his extraordinary capacity for consumption (if not gluttony), along with his utter inability to judge qualities or even to discern them; but most of all his egocentrism and the fatal alienation from the world that he mistakes for self-alienation (this, too, dates back to Rousseau)—all of this first manifested itself in “good society,” which does not have a mass character. The first people of the new mass society, one might say, constituted a mass to such a small degree (in a quantitative sense) that they were actually able to consider themselves an elite.

One could argue that, with a few exceptions in Northern Europe, Americans represent the elites of the world. We are enmeshed in the ills outlined in this dense paragraph from Arendt’s critique of mass society, and it is natural to crave for some sort of spiritual solace. Most of us in Tysons Interfaith would probably quibble with the word “solace,” because that seems like a psychological cop out. Our faith traditions emphasize the Platonic world view that ideals, like good and evil, are real.

I believe that the beauty of religious worship is its communality. Megachurches excepted, most worship takes place in an intimate setting where loving relationships can be forged between individuals of different backgrounds and tendencies. This is what I experience in my faith community and with my participation in Tysons Interfaith. If you want to read about communality in action, I recommend to you the life of Gordon Crosby, who bucked the trend of bigness and put social responsibility front and center in his theology. Rebel pastor Gordon Cosby left lasting mark on mainstream Christianity – The Washington Post.

On a recent road trip to the west, we stopped in Columbus, Ohio. Among other things, we saw the Ohio Capitol building, which was beautiful and distinctive, especially at night. [Interesting fact – You might think they didn’t finish the dome, but the horizontal top was on purpose, to reflect the Greek Revival style to honor the Greek concept of democracy, whereas domes are more Roman style.]

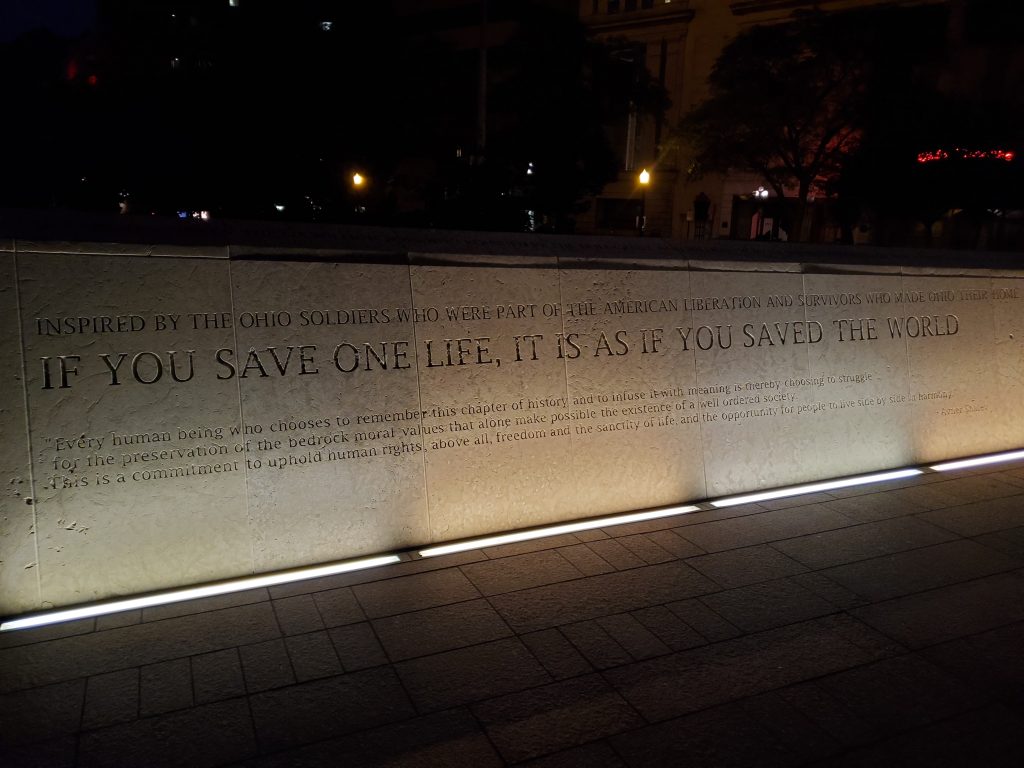

One thing we didn’t expect was a Holocaust and Liberators Memorial on the Capitol grounds. Apparently during a Holocaust remembrance ceremony several years ago, the governor was so moved he said the state needed a more formal Holocaust Memorial, so one was commissioned. It is solemn and powerful, as you can see from the pictures (we thought particularly moving at night).

The memorial speaks for itself, but we were particularly inspired by the timeless quotes on the marble wall leading to the monument:

“If you save one life, it is as if you saved the world.”

“Every human being who chooses to remember this chapter in history and to infuse it with meaning is thereby choosing to struggle for the preservation of the bedrock moral values that alone make possible the existence of well-ordered society. This is a commitment to uphold human rights, above all, freedom and the sanctity of life, and the opportunity for people to live side by side in harmony.”

For more information on the memorial, see, http://www.ohiostatehouse.org/about/capitol-square/statues-and-monuments/ohio-holocaust-and-liberators-memorial. We particularly recommend the story of Michael Schwartz which is inscribed on the main part of the memorial.”

“The zealously nurtured attitude of literal credulity towards the oriental treasure of thought is in this case a lesser danger, as in Zen there are fortunately none of those marvelously incomprehensible words, as in Indian cults. Neither does Zen play about with complicated Hatha-yoga techniques, which delude the physiologically thinking European with the false hope that the spirit can be obtained by sitting and by breathing. On the contrary, Zen demands intelligence and will-power, as do all the greater things which desire to become real.”

Thus, no less a thinker than Carl Jung ends his foreword to D.T. Suzuki’s essays on Zen, first published in Japan during the “1914 War.” The eminent psychologist takes more than twenty pages to dance around an explanation of what the Japanese call Satori, translated imperfectly as “enlightenment” in most “Western” treatises. If he can’t do it, with all the usual qualifications, then how can a hopelessly European male living on the outskirts of Tysons do so in the 21st century?

Well, let’s start with a classic Wu- or Mu-anecdote about the dog. A monk once asked: “Has a dog Buddhist nature, too?” The Master answered: “Wu,” which Jung explains is “obviously just what the dog himself [in my case, herself] would have said in answer to the question.” It usually comes out as “woof.”

Without “making any recommendation or offering any advice,” Jung says that when Westerners begin to talk about Zen, he considers it his “duty to show the European where our entrance lies to that ‘longest of all roads’ which leads to satori, and what difficulties strew that path, which has only been trodden by only a few of our great men [sic]—perhaps as a beacon on a high mountain shining out in the hazy future.” It “can neither be captured in with skillful formulae nor exorcized by means of scientific dogmas, for there is something of Destiny clinging to it—yes it is sometimes Destiny itself, as Faust and Zarathustra show all too clearly.” Well, it’s not so clear to me since I don’t really understand German.

He goes on to warn that these two great works “are only on the border-line of what is comprehensible to the European” and “one can scarcely expect a cultured public who have only just begun to hear about the dim world of the soul to be able to form any adequate conception of the spiritual state of a man [sic] who has fallen into the confusions of the individuation process, by which term I have designated the ‘becoming whole’ (Ganzewerdung).”“Preoccupation with the riddles of Zen may perhaps stiffen the spine of the faint-hearted European, or provide a pair of spectacles for his short-sightedness, so that from his ‘gloomy hole in the wall,’ he may enjoy at least a glimpse of the world of spiritual experience, which until now has been shrouded in mist.”

Well, I can tell you that early in the morning on the Jones Branch Extender by the Capital One building, there are indeed mists to contemplate. And there are plenty of dogs being walked about by happy denizens all around Tysons. So, woof. Or should I say, “Wu”….?

In December, when I started at Emmanuel Lutheran in Vienna as their associate pastor for evangelism and mission, I joined Tysons Interfaith right away. As someone entering my 10th year of ordained ministry, I have been part of a few ecumenical groups over the years, but this one is unique. As I attended our zoom meetings over the last year and participated in TI’s various discussions and forums, I’m so inspired by the work and passion that is happening in this group, despite the pandemic and its limitations.

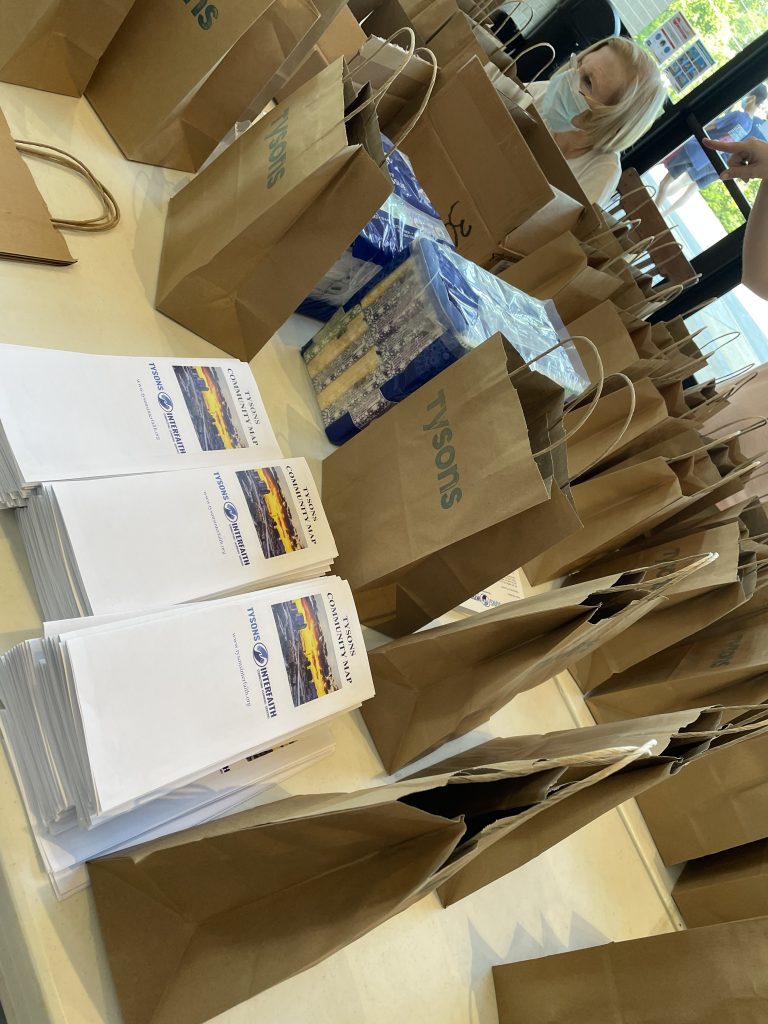

At the end of July, I was finally able to meet some of the other members of Tysons interfaith in person, at Redeemer Lutheran in McLean to assemble “Welcome Bags” for new residents in Tysons. Our idea is to provide these bags to many of the major condominiums and apartment complexes in Tysons, to give away as new people move in. Inside each bag is a pen, magnet and lens cleaning cloth with the TI logo, a map of the community that includes a list of congregations in the surrounding area, a metro map, and a small package of tissues (because, pandemic!). We hope that new residents not only feel welcomed and connected to the community, but also learn that TI and these faith communities are ready resources. These bags will be going out in the next few weeks, to create a sense of connection and inclusion to the newcomers in our midst.

As someone still fairly new to NOVA, I’m so appreciative to have this group of passionate colleagues to work along with, and I am relieved that none of us are doing this alone. As a Christian and as a Lutheran, I believe that God is already present and at work in the community of Tysons, and God is continually inviting us alongside this work, as fellow participants. I’m thrilled to be along for the ride!

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

A recent BBC program reported on the controversy surrounding the “residence schools” established in Canada to “wring the Indian out of indigenous children.” Publicly funded, the schools were mostly established and run by the Roman Catholic Church and did not finally disappear until the 1990s. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000xzdm

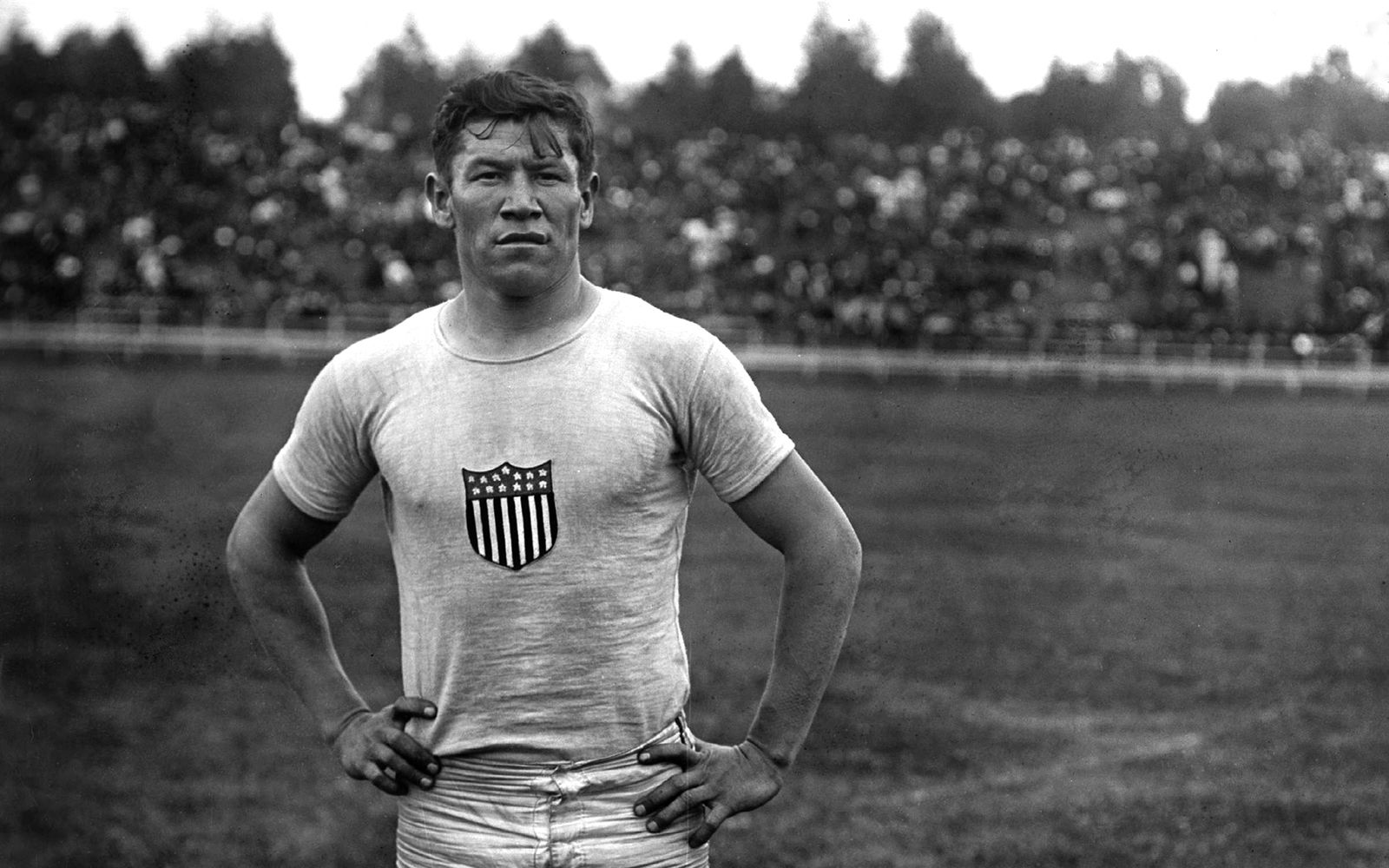

I first learned about the U.S. version of this program when I participated in the annual “Jim Thorpe Day” competition at the Army War College in Carlisle, PA, the site of Thorpe’s on-again, off-again alma mater (he had trouble staying in school). Thorpe became an Army legend, possibly America’s greatest Olympic and professional sports champion ever and, lesser well known, a successful Hollywood actor. https://www.vice.com/en/article/z4d74a/a-thanksgiving-reminder-jim-thorpe-is-a-native-american-hero

Despite a bit of European ancestry, Thorpe was generally regarded as wholly American Indian, which made him both a curiosity and an advertisement for assimilationist policy. The founder and head of the Carlisle school, for example, believed that Native Americans must convert to Christianity and seek an education to prepare for success in the dominant culture. He once wrote that the U.S. government must “kill the Indian…to save the man.” His hubris, and a lack of proper oversight led inevitably to cases of physical, mental, and sexual abuse, only some of which have been belatedly prosecuted. Run by secular staff from the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Protestant religious organizations, or Catholic religious orders and parishes, the schools were part of what many call a program of “cultural genocide.”

Thorpe did not talk about this, but during his Hollywood career – he appeared in more than 70 films – he earned the title “Akapamata,” which in his Sac and Fox heritage means “caregiver.” His experience as co-founder and first president of what became the National Football League came in handy when he approached the BIA for a grant to launch an “Indian Center” in Los Angeles.

Together with a Native-American partner, Cecilia Blanchard, Thorpe formed what Blanchard’s great-granddaughter called a ‘Welcome Wagon’ for the Native peoples streaming in from all over. https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/akapamata-forgotten-hollywood-legacy-jim-thorpe. They would match the new arrivals with casting calls and auditions and, unwelcome in the city, organize Saturday-night potluck gatherings on the outskirts of town where the women used a traditional “dinner fire” to cook the game the men cleaned. All this eventually led to the Native American Actors Guild, formed because the Screen Actors Guild was even less welcoming than the Angelinos.

In the words of Blanchard’s great-granddaughter: “The industry was racist. They were portraying a vanishing people and a dying culture, and they were portraying it over and over again. That wore on the Natives’ psyche. That wore on their hearts. We are a proud people. We have worked hard to survive. Jim realized this and knew he had the best agency to create change. He tried to offer them an opportunity to be more than society was telling them they were going to be…. He went to his grave fighting for equal pay for Native actors and decent health insurance, especially for the stuntmen! Jim’s valiant effort laid the early groundwork for the benefits enjoyed today by indigenous people in the industry where we are still trying to crack the glass ceiling of film and media and taking back control of who we are as a people.”

Reflecting on the life and legacy of Jim Thorpe, I think he was an American hero on the order of Jessie Owens and Jackie Robinson, a man who could be embraced by Americans of any background. He is revered by the Army because he adopted its values of loyalty to service and country, action on the field of battle, and the performance of great deeds. He was embraced by most of his countrymen despite his Native American background and ongoing controversy and contradictions. These include his lifelong battle with alcoholism; his fraught marital life; the infighting among his heirs over whether he should be buried in the Pennsylvania town that took his name or back in Oklahoma on his ancestral lands; and the embarrassment of having the International Olympic Committee first strip him of his track and field medals because they found out he had played semi-professional sports and only posthumously reversing their decision. He had matchless God-given talents, but he also benefitted from the unique teaching and coaching that helped mold his individual talents into greatness. It is impossible to ascertain whether our efforts to wring the Indian out of him resulted in Jim Thorpe being more Christian and “American” than what he most certainly was: a hero of the Sac and Fox nation.

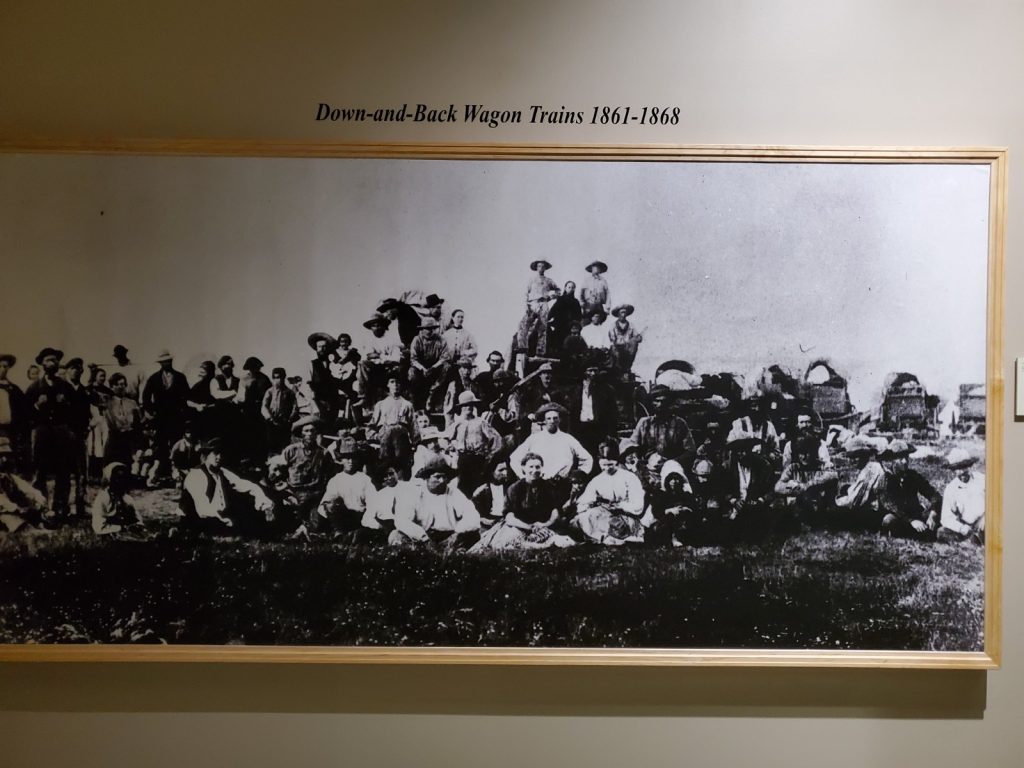

Every July 24, the State of Utah celebrates Pioneer Day, a major state holiday. Pioneer Day commemorates July 24, 1847, when an early contingent of Mormon pioneers, led by Brigham Young, entered what is now the Salt Lake Valley. They had made a long trek to find a place of refuge from religious persecution. The holiday is marked in many Utah cities and towns by a parade with pioneer-themed floats.

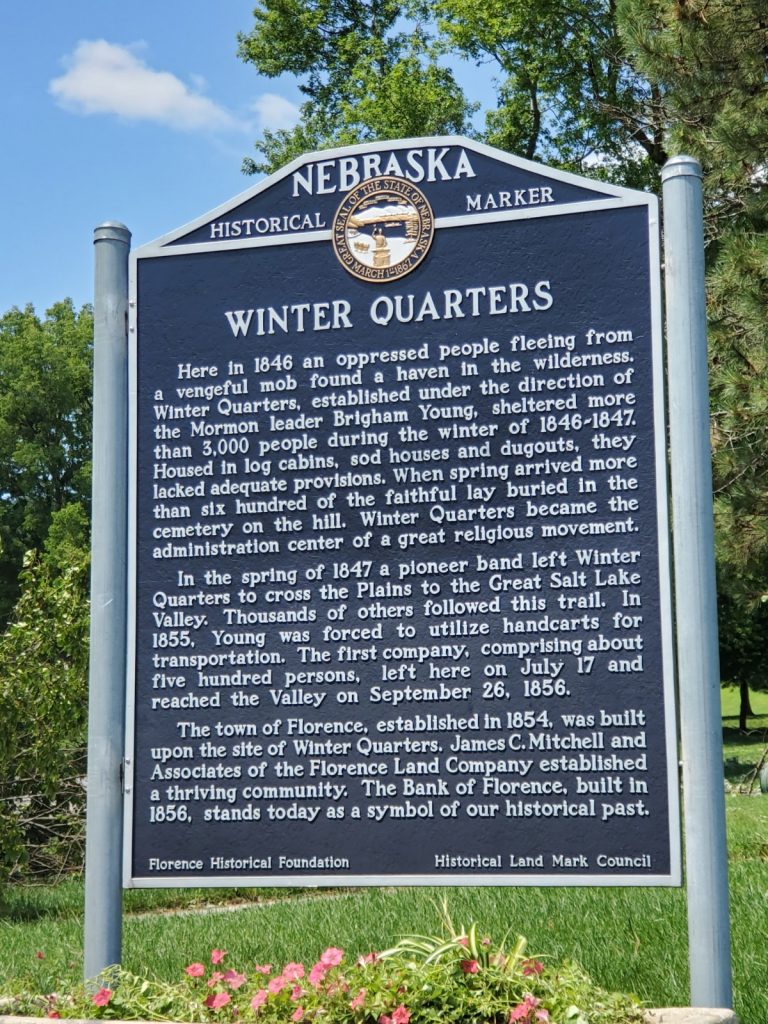

On a recent road trip through the West, we saw some key points along the trail that led to the settlement in Utah. The first was Winter Quarters (current day Omaha), the embarkation point where the Mormon pioneers spent two winters preparing for the trek west. Downtown Omaha has an extensive monument to the Mormon and other pioneers that went west in wagons, on horses, or on foot pulling handcarts. There is also a cemetery where 600 of the 4,000 Mormon pioneers who spent those difficult winters are buried – they didn’t make it west. Overlooking the cemetery is a powerful bronze sculpture commemorating the sacrifices and faith of those pioneers – by sculptor Avard Fairbanks, who coincidentally sculpted the busts of George Washington that frame the campus of George Washington University. The sculpture is placed directly over the graves of an unknown child and seven other pioneers.

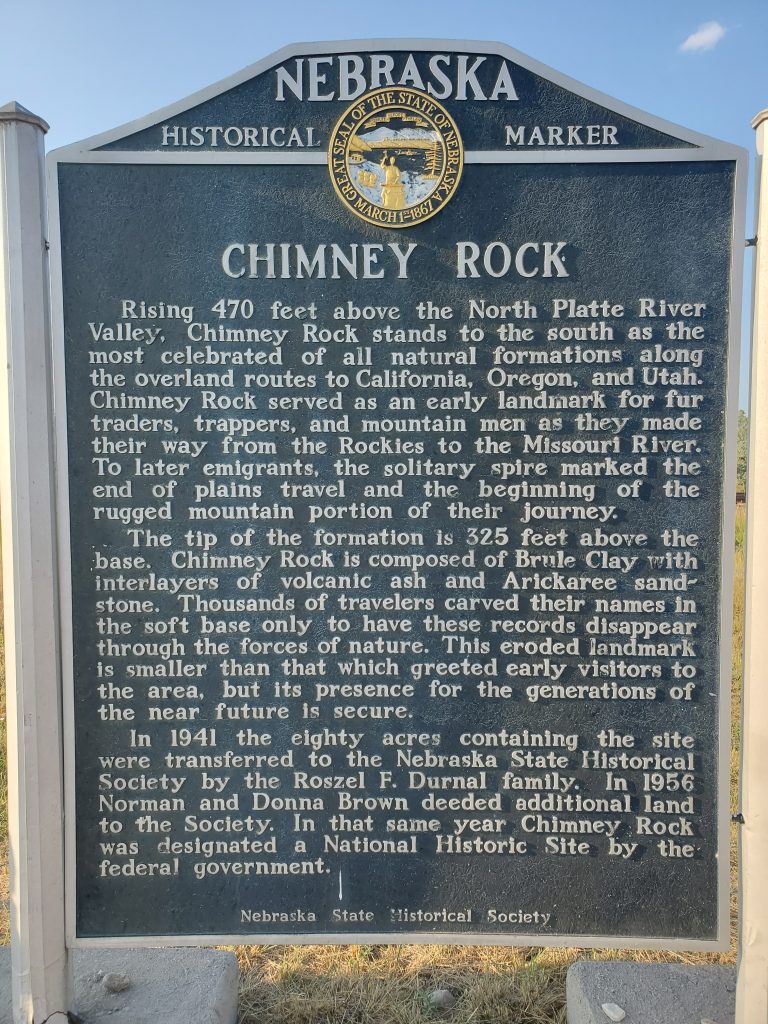

About 450 miles to the west is Chimney Rock in the North Platte River Valley. Not only is it the most recognizable landmark on the Mormon Trail (and the Oregon Trail that parallels it) because of its unique shape, it also marks the end of the flat part of the trail and the beginning of the mountainous terrain that culminates in the Rocky Mountains. Near Chimney Rock is a grave marker for Rebecca Winters, a mother of 4 who died from cholera along the trail. It was very moving to see that a family friend had taken the effort to carve her name in an old wagon wheel to memorialize her sacrifice and her importance as an individual. Her descendants later added a more traditional grave marker.

The Mormon Trail is sacred ground for members of our church, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Both of us have ancestors who were among the 70,000 that went west, through great hardship, to find a place of peace to live and worship. What motivated these pioneers to make this dangerous trek? As one of our church leaders summarized a few years ago:

“The foremost quality of our pioneers was faith. With faith in God, they did what every pioneer does – they stepped forward into the unknown: a new religion, a new land, a new way of doing things . . . Two companion qualities evident in the lives of our pioneers, early and modern are unselfishness and sacrifice.”

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.