Contributed by Susan Posey, Redeemer Lutheran, McLean

In a world where troubling news abounds, Tysons Interfaith is dedicating 2026 to highlighting “What’s Going Right.” Whether it is individuals, organizations or nations working to improve the lives of others and to build a just and peaceful future for all of us, there is always good news to be found.

We hope the following blog post will bring you encouragement and inspiration to make a positive difference in your own corner of the world.

This week, Ramadan began for our Muslim brothers and sisters, and the season of Lent began for many in the Christian community. As we enter this time of reflection, I hope all (however we experience the Divine) will remember the remarkable journey of the Buddhist monks who recently completed their 2,300 walk for peace.

Their message for individual and collective peace seemed to resonate with people they encountered on the 108-day walk. In deed, people were hungry for it. The ceremony welcoming the monks to National Cathedral on February 10 was attended by thousands of people, including faith leaders from all types of faiths.

In his remarks at National Cathedral, the Venerable Bhikkhu Pannakara concluded that he hopes the message of peace the monks carried is something we will unlock in our own hearts and minds every day.

There are many press accounts about the monks’ incredible journey. Here is just one:

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/buddhist-monks-15-week-walk-peace-ends-washington-dc-rcna258458

To view the ceremony held at National Cathedral on February 10, please visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C5lbugF8PHY

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Rev. Dr. Trish Hall

Have you ever felt totally out of control—like a cartoon character clinging desperately to a wildly spinning object? Or as if you were possessed by some external force, only to discover that the force was actually inside you? At times, emotions can feel like being sucked into a vacuum—one that swirls everything in its path with no regard for what remains standing.

Emotions are powerful. They can cripple or empower. They can paralyze or energize. And during times of upheaval—when what once felt safe and predictable has been overturned—we may forget that we hold within us the capacity to redirect that force. We can transmute emotional chaos into purposeful energy. We can pause, ask, How am I to serve?—and then listen for what wants to emerge through us.

We humans are fascinating creatures. We work relentlessly to make sense of our world, especially when it stops making sense. When life turns upside down, we fight to restore equilibrium—to reestablish a reality where up is up and down is down. We are meaning-making machines, trying to reason our way through the unreasonable.

Often unconsciously, we construct stories that explain why what feels wrong isn’t really wrong—or why it must somehow be justified. We can sustain these narratives for a while. Eventually fatigue sets in. Beneath our explanations we discover fear: fear that life will never return to “normal” (if such a thing ever existed). We grieve the loss of what once anchored us. And for many, anger rises—often directed toward whoever or whatever we believe caused our losses or threatened our sense of safety. Others turn inward, sinking into despair or depression.

This emotional mélange describes the inner world of countless people right now.

Yet there is another remarkable quality woven through our fear, grief, and anger: resilience. It is our survival instinct—the deep intelligence that keeps us moving forward even when certainty dissolves. Emotions themselves are part of that intelligence. They are not flaws in our system; they are the system—internal alerts signaling that something is out of balance, that we no longer feel safe or oriented.

When these alarms sound, our bodies constrict. We feel compelled to defend ourselves and those we love. We cling tightly to the life we once knew, even while doubting whether equilibrium can ever be restored. And yet, paradoxically, it is often in these very moments of instability that our greatest inner strength is revealed. Crisis has a way of calling forth capacities we did not know we possessed.

Many of us were taught to categorize emotions as “good” or “bad.” But emotions are neither. They are intelligent signaling mechanisms—information carriers. What matters is not the emotion itself, but how we interpret and use the information it provides.

Emotional data deserves discernment. Our feelings are filtered through personal history, cultural conditioning, and unconscious bias. Five people can witness the same event and experience five entirely different realities. Likewise, our emotions do not always reflect objective truth. Add to this our innate tendency toward confirmation bias—the inclination to notice what confirms what we already believe while filtering out contradictory evidence. It becomes clear why emotions can feel so convincing in spite of lacking accuracy.

Because we assume something to be true, our emotions react in anticipation of that assumption being fulfilled, reinforcing the belief and strengthening the emotional response. This feedback loop can trap us—unless we pause long enough to examine it.

When we release the habit of labeling emotions as good or bad, a deeper understanding becomes possible. Emotions are energy. And energy can be directed.

Anger, for example, can be paralyzing—or it can be a source of immense strength. We can hand our power over to it, allowing it to rage unchecked, or we can harness its energy to challenge systems that no longer align with our values. The difference lies in conscious choice.

So the real question becomes: Are we willing to remain victims of our emotions, or are we ready to work with them as allies? Are we frustrated enough with being overwhelmed that we are willing to reclaim our power?

Personal transformation is not for the faint of heart. It requires courage, commitment, and a willingness to step into the unknown. Imagine how different life could feel if you were no longer imprisoned by your emotional reactions. Freedom begins when we learn to redirect emotional energy rather than suppress or discharge it.

Fear, grief, and anger each arise from a perceived loss—and each contains an embedded calling.

Fear emerges when the structures we trusted collapse—when our ability to discern what is safe feels shattered, and we believe ourselves powerless against forces beyond our control. Grief surfaces when the loss feels final—when hope dims and helplessness deepens isolation. Anger arises as a demand for change, an eruption of pent-up energy seeking movement and expression. Frustration often speaks through anger, which—when channeled consciously—can be profoundly constructive.

To uncover the wisdom within these emotions, we must ask a different question: What would I rather experience? This shift in perspective opens a powerful truth—we already possess what we need to change direction. While we cannot control how others respond or whether the world conforms to our desires, one thing is absolute: when we change, our world reorganizes around that change.

This realization is profound. When we declare “enough is enough” and draw upon our inner strength, we discover that we are not broken—we are latent potential waiting to be activated. As Mother Teresa reminded us, “Not all of us can do great things. But we can do small things with great love.”

Within fear lies the desire to rebuild trust and restore connection. It calls us toward community, collaboration, and service—toward groups that identify needs and work together to meet them.

Within grief lives empathy—the capacity to sense what others are enduring. It invites us to nurture, to accompany, to bring tenderness where there has been harm.

Within anger resides the energy for change. Mobilized anger becomes action: marches, advocacy, prayer circles, meditation gatherings, visible stands for justice and healing. Mobilization simply means movement—transforming frozen rage into purposeful engagement. Healthy anger requires healthy outlets.

Each of these emotions carries transformative potential. Grief can deepen compassion and meaning, allowing sorrow to be felt without drowning in it. Fear can sharpen discernment, draw us into presence, and cultivate trust rooted in clarity rather than denial. Anger can bring focus, agency, and healthy boundaries, helping us identify what must be protected or changed.

The invitation is ours: to choose conscious outlets and step into action.

One way to begin is through reflection. Recall people or situations that have brought out your truest self. Who were they? How did they show up? What about them called to you? These attractions are not accidents. They signal alignment. Something within you recognizes something possible.

Allow images of work, service, or volunteer opportunities that embody these qualities to surface. Compare their attributes with what brings you joy. Then invite the emotional energy that once held you captive to fuel engagement—especially in forms of service that involve giving of yourself.

Research consistently affirms what many of us intuitively know: when we give from the heart, we receive profound benefits. Volunteering is associated with reduced anxiety and depression, increased life satisfaction, greater emotional resilience, enhanced social well-being, and improved overall quality of life. Emerging research even suggests links between consistent community engagement and slower cognitive aging.

Perhaps most importantly, service shifts our orientation from self-absorption to being a beneficial presence.

Our emotions are not obstacles to overcome. They are invitations. When we listen deeply, redirect wisely, and act courageously, fear, grief, and anger become pathways—not prisons—guiding us into lives of meaning, connection, and purpose.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Rev. Dr. Trish Hall

“The mysterious path of spirituality is a path to the intangible. Human beings are used to the tangible. From tangible to intangible and knowing to the unknowable, the path is quite treacherous and often winding. There are many trials and errors possible. Many falls and rises. Tenacity and conviction plus the will to survive against all odds will keep us going. It is a long and winding road by itself.”

The Path of Pathlessness … Mohanji

We humans spend most of our time living circumstantially, reacting to our environment – physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually. Feeling a sense of discontentment, we are drawn to search, to what Ernest Holmes called “The Great Search.”

“The world seeks a solution of its great riddle—the apparent separation between God and man; between life and what it does; between the invisible and the visible; between the Father and the Son—and until this riddle is solved, there can be no peace. Peace is an inner calm, obtained through man’s knowledge of what he believes and why. Without knowledge, there is no lasting peace. Nothing can bring peace but the revelation of the individual to himself, and a recognition of his direct relationship to the Universe. He must know that he is an eternal being on the pathway of life, with certainty behind him, certainty before him, and certainty accompanying him all the way. Peace is brought about through a conscious unity of the personal man with the inner principle of his life—that underlying current, flowing from a divine center, pressing ever outward into expression. But this can never come by proxy. We can hire others to work for us, to care for our physical needs, but no one can live for us. This we must do for ourselves.”

We intuitively seek Peace. Both Dr. Holmes and Mohanji caution that we should not assume that it will be easy, yet we have within us everything we need to make the journey. We must make the journey for ourselves – we are the only ones who can.

The challenge that I lay before all of us is, are we willing to release the known, the visible, that which we believe with certainty in order to experience Divine Peace? Do you trust the process deeply enough to venture into the realm of the pathless?

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Rev. Dr. Trish Hall

At Centers for Spiritual Living, our core belief is Oneness – the inseparability of all creation.

“We believe in God, the Living Spirit Almighty; One indestructible, absolute, and self-existent Cause. This One manifests Itself in and through all creation but is not absorbed by Its creation. The manifest universe is the body of God …”

All Creation is the result of the Creator expressing Itself in form. Its activity is Love. Within the One we are inseparable from one another – those we love and like and those we don’t like and yet are called to love.

We believe our world is the manifestation of God. There is nothing else so the Allness of God includes everything. Everything is within this One Creation. Within this creation are people and things we love and try to understand, and people and things that we find incomprehensible. It includes people we do not like and those we deem to be unlikable.

The task of loving those we have labeled unlikable varies from relatively insignificant to paralyzingly daunting. Our world view tends to dictate how we relate to all people – the likables and the detestables. Our emotional responses may vary from casually acknowledging that some people do not appeal to us or hold views that are incompatible with ours, to finding ourselves triggered having gut-level reactions and fear. The call to love our neighbors isn’t subject to our emotional responses. The call is clear and is not to be ignored.

Before looking at loving “the unlikable” we need to consider “unlikability.” How is it determined and by whom? The dictionary tells us that unlikable is detestable, despicable, contemptible, worthless. I ask based on what criteria? I invite you to contemplate the difference between UN-likable, which seems to focus on the nature of the person, versus DIS-likable which seems to relate more to the temporariness of behaviors. So far, I have not met a parent who hasn’t shared that there have been times when they really didn’t like their offspring yet never wavered in their love for that child. They didn’t declare that child unlikable, they disliked the behavior and loved their kid. Dislikable then seems to be redeemable, whereas someone deemed unlikable is inherently flawed.

Likeability is subjective. It is an opinion formed by an individual that then is spread to that person’s circle and ripples out coalescing the perceptions of greater numbers of people. Interestingly, the process works whether positive or negative. It is used by celebrities of all kinds. The process is impartial. History is fraught with examples of how the same process has been used destructively. Instead of uplifting someone or moving some great cause forward, it has been used in the opposite direction to impose misery and injustice. The process can engender mob mentality. All it takes is someone deciding something about someone and spreading their opinion about that person (aka gossiping), stirring up mobs of like-minded people into acts of violence. You may say those are extreme examples, and I will challenge that the pattern that conducted witch hunts in the 15th to 18th centuries, is as alive and well today as it was then. It was a demonstration of raging prejudice then. It remains a demonstration of raging prejudice now. The focuses of the prejudgments may have changed; the resulting behaviors have not.

How is unlikableness determined? By whom? On what criteria? Is there an unlikableness scale? Where do you get the information on which you have formed your opinions?

I invite you to examine your own beliefs – to challenge them – to form your own opinions whether or not they are compatible with your family and friends.

Let’s start fresh. Let’s begin by honoring what we are and why we have the ability to decide what is right for us personally. As Jane Goodall said, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” It is your right to choose to not examine your beliefs, to conform to some external expectations and remain as you have been. And you have the right and the privilege to decide to change radically or anywhere in between. We are blessed that we have those options. We have those choices because we are endogenous beings – our origin is internal rather than dependent upon external forces. We are thinking beings that have the power to choose our own courses of action. I believe that exercising that privilege is our responsibility.

As believers in Oneness, is there a space for anyone to be judged unlikable? Perhaps, very dislikable?

Preparing for this self-examination, a first step might be to look closely at our own criteria. Is it a reflection of the society in which we live or our personal values? Have you reviewed the input of others (media, relatives, etc.) to determine whether it is in alignment with your values – with how Spirit within you is calling you to be?

Oneness assumes that everyone and everything is the expression of One Creator. Different traditions have given this one creator myriad names. The names can limit our perceptions – our assumptions about it. They cannot limit the Creator. Oneness asks us to accept that it includes what we understand and what we don’t, what we like and what we don’t, what we love and what we don’t. Oneness calls us to be so open that we can be in the midst of apparent disparities and contrasts and learn strategies to live in peace celebrating diversity within the Oneness. Oneness invites us to be in integrity and live into the change we want to experience. Some tough questions remain: Are our hearts big enough to hold a space for those whose behaviors appall us without judging them to be inherently (perhaps permanently) flawed? Can we expand our concepts of being present with those we do not understand so that we can learn from them while remaining grounded in Love? Are we willing to be open to the possibility that we can create a world that works for all especially when it requires collaboration with the dislikables? Are we bold enough to be peace makers in the midst of the antithesis of peace?

Jane Goodall declared, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” I ask, Do you have the courage to stand as Oneness, as a Peace Builder … to be a change-maker?

To learn about the Centers for Spiritual Living’s Global Heart of Peace Initiative, please visit: https://csl.org/spiritual-community/heart-of-peace/.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

Spurred by a comment to my blog post on “comfort,” led me to take a historical and philosophical dive. In 2014 Philip Jenkins wrote a deliberately provocative article to argue there was “a genuine and epochal decline in the number and scale” of religious movements like the Church of Scientology and the Unification Church, both of which date from the 1950s and early 1960s.

But others have mushroomed in Asia, where I lived and worked for years. Daesoon Jinrihoe, founded in 1969, is the largest “new religion” in Korea, while the Church of Almighty God – you can’t make these names up — was established in 1981 in China and claims millions of followers at home, and because of persecution and emigration in some 20 other countries. Indonesia, Vietnam, Africa, Puerto Rico, and Columbia have spawned “new” religions or neo-Pentecostal groups. Mexico’s La Luz del Mundo has spread despite COVID-19 and the arrest of its leader for a sexual crime.

The new Korean religions usually cite Christianity as a source and are often more successful abroad than at home. Just so, the World Mission Society Church of God claims two million members in Nepal, Latin America, and even in the United States, where the Unification Movement has dwindled to 65,000 members but controls the wholesale sushi supply industry and a newspaper. Won Buddhists and Jeungsanists have recently translated their texts and begun missionizing abroad, which some see as unprecedented in religious history.

Why do we need religion, new or old?

In 1949, Karl Jaspers posited the idea that there was an “Axial Age” from roughly BCE 800-200 when humans, across vastly different regions and without direct contact, simultaneously came up with new ways of thinking that lay the foundations for the world’s enduring philosophical, moral, and religious traditions. These included China, where Confucius and Laozi (Taoism) reshaped ideas on ethics and governance; India, where the Buddha, the Upanishadic philosophers, and the Jain tradition emphasized liberation, compassion, and self-realization; Persia, where Zoroaster, introduced dualistic cosmology and moral responsibility; Greece, where Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle explored reason, ethics, and metaphysics; and Palestine/Israel, where figures like Isaiah and Jeremiah deepened the moral and spiritual vision of Judaism.

Jaspers has been criticized for simplifying things, but many agree there was a process if not an “Age” where a new layer of morality emerged that featured the following principles:

1. Moralistic punishment: violations of “natural” morality will be punished by higher authorities, in this life or the next.

2. Moralizing norms: peers and other members of a relational network are obliged to monitor and deter deviance.

3. Pro sociality: cooperative behavior should be actively encouraged and rewarded.

4. Moralizing supernatural beings: an “eye in the sky” watches over everyone, punishing sins and rewarding virtuous behavior.

5. Rulers are not gods: worldly leaders are merely human, just like everyone else.

6. Equality: moral rules apply to both elites and commoners, regardless of birth and social status.

7. Ruling morality: The rules apply to the rulers as well.

8. Formal legal code: the rule of law is explicitly formulated.

9. General applicability: the law applies to all citizens equally.

10. Constraints on the executive: decisions are constrained by formal rules—such as a veto—or informal (but powerful) ideological constraints, e.g. requiring the tacit approval of a priesthood.

11. Bureaucratization: administration of a system of governance requiring specialist skills, training, and salary.

12. Impeachment: excessive and arbitrary exercise of power by rulers can lead to their removal.

This new morality replaced “archaic” systems where rulers could act with impunity. Again, however, there were exceptions. In the Italian Peninsula, Christianity created a pronounced moralizing dimension, but it was accompanied by an increase in social inequality – still not as bad as in the old Roman Empire — and the emergence of a religious autocracy. Moreover, the greatest concentration of axial principles was not in the first millennium BCE, but in the 2,000 years that followed. Because of the emperors’ strong association with the divine and a lack of tension between secular and sacred order, Japan remained pre-axial until the modern era despite early introduction and adoption of Buddhist and Confucian ideas. And in what is now Cambodia, Buddhism and the Hinduism that preceded it did not exercise a moralizing effect until much later.

Archaeological and historical research in the decades since Jaspers, moreover, has unearthed evidence for “sustained, impactful connections between all of these regions.” Zoroastrianism, Rabbinic Judaism, and Greek philosophy not only developed through the exchange of ideas, but also owed much to earlier Hittite, Mesopotamian, and Egyptian ideals and practices.

But what about the newest religions? Several theories share the idea that after the French and Industrial Revolutions, rapid change and the feeling of an “accelerated history” provided fertile ground for such movements. They argue that it is not a coincidence that Spiritualism and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints appeared first in 19th century New York and that some Asian countries, faced with imperialism, colonization-decolonization, war, and sudden economic development have similar experiences.

Fast forward to Korea, where the social unrest caused by Japanese, Chinese, Russian, and Western imperialism helped spread the idea that Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism were outmoded. Christianity and Ch’ŏndogyo, Daejongism, and the branch of Jeungsanism known as Bocheonism gained followers because they opposed Japanese occupation. After the devastation of the Korean War, new groups proliferated and became even larger. And they continue to this day.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Lois Herr — First Church of Christ, Scientist, McLean

Many people set aside time in their day for prayer, reflection, or meditation. As a Christian Science practitioner, I often find inspiration in daily audio reflections presented by members of our church, called the Daily Lift.

A recent Daily Lift by Madora Kibbe, a Christian Scientist Practitioner and teacher from New York, New York, is entitled, “Why Would You Love An Enemy?” In this segment, Madora notes that the Sermon on the Mount (the manifesto for peace) in the Christian Bible directs that we love our enemies – “and that is hard!” To illustrate her point, Madora shares a touching vignette about her father, who served in World War II. She concludes that because we are all manifestations of the spirit of our creator, it is our duty to separate wrongdoing from people. For Madora, loving our enemy, is indeed, the only real answer.

The Daily Lift is comprised of audio presentations contributed by Christian Science church members worldwide – with the majority coming from the U.S. This particular Lift will remain on the website for thirty days before being retired.

May this segment bring you peace and encouragement.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman: St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

“What would they do if they were tested with a great tragedy, wouldn’t they need God for comfort?”

That was the question asked by one of our Baha’i friends at last week’s Interfaith Coffee House (please come!) in response to my snarky suggestion that, looking at the lives of my son and his wife and daughter at least, one doesn’t have to believe in God or practice a particular faith to lead a good and contented life. It got me thinking.

It’s not always the need for comfort that brings us to God, although there’s a long strain in Christianity that sees this. In fact, listening to a BBC broadcast about prison conversions the other day, I was struck by how these events occur most often when a person is at their lowest ebb.

But then there is the case of Saul on the road to Damascus: the man who became Paul knew in his heart that persecution was not God’s will. Justice, humanity, and love for one’s enemies – not comfort – was the basis for his conversion. Of course, when Paul was imprisoned in what is now Turkey, he led his fellow prisoners in hymns to God even as they experienced a massive earthquake. He told them to take comfort in the Lord and not to escape and ended up converting their jailor!

If you examine the life of Christ or Buddha or perhaps of other religious leaders, “comfort” is not the first word that comes to mind. They struggled often, and almost as frequently they called us to live a life of discomfort. As Jesus put it in Matthew 10:

‘Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.

For I have come to set a man against his father,

and a daughter against her mother,

and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law;

and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household.

Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me. Those who find their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.’

Not exactly a message of comfort.

But I’m sure our Baha’i colleague had something else in mind when he used the word “comfort.” In the face of adversity, one can indeed take comfort in the assurance that God is with you and that someday soon this will be overcome. That’s what motivated Paul in captivity, and that’s what has helped so many in the world overcome injustice.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

“Why Have Empathy for Those Who Never Extend It?” is how Qasim Rashid begins a brave essay that reflects on the death of Charlie Kirk Reflections on the Death of Charlie Kirk. It is well worth the time to read his thoughts in full, but here is a summary:

Rashid argues that Kirk rarely extended empathy and often poured contempt on many groups of Americans, including Muslims, engendering hatred.

And he returns to a verse from the Qur’an for guidance:

“O ye who believe! be steadfast in the cause of God, bearing witness in equity; and let not a people’s enmity incite you to act otherwise than with justice. Be always just, that is nearer to righteousness. And fear God. Surely, God is aware of what you do.” — Chapter 5, Verse 9

Rashid detests and works ferociously to counter what he views as the hatred that Kirk engendered but at the same time does not allow these injustices to make him retaliate in kind. As he puts it: “I will not allow his fear of the other infect my ability to see the humanity in every person.”

And here is an important comment from the niece of Rev. Martin Luther King:

‘And now while his family and this nation grieve, some are calling him a racist. A white supremacist. Even a fake Christian. Such accusations are conversations unbecoming to a Christian,” she continued. “In the final analysis, Charlie stood for life, for faith, and biblical truth. He wasn’t afraid to say the name of Jesus in the public square, and he paid a price for it. Now is not the time to attack Charlie. It’s the time to lift up the banner of Christ as the member of the one blood human race Charlie Kirk did. His legacy of public discourse of bringing difficult conversations to the table mattered. He caused us to think and to pray. Charlie has gone to meet his maker. May he rest in peace. May we honor him today by praying for his family and by answering this question: Where will you spend eternity?’

“Such empathy or hard “love” is a basic premise of all our faith traditions. I disagree with Kirk on most things, but especially on his treatment of the LGBTQ community, Muslims and “progressives,” but like Rashid’s, my faith requires me to respond with kindness even as I express my disagreement.

In the Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church, there is a prayer for one’s “enemies” that carefully balances responsibility on both sides of a conflict:

“O God, the Father of all, whose Son commanded us to love

our enemies: Lead them and us from prejudice to truth:

deliver them and us from hatred, cruelty, and revenge; and in

your good time enable us all to stand reconciled before you,

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

In that spirit and in the spirit of Islam and other faith traditions, let us extend our empathy and love, without prejudice, to the Kirk family and his supporters.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

This past summer at McLean Baptist Church we did a series of Sunday morning group studies titled ‘Kaleidoscope of Faith.’ I had the pleasure of presenting the last session of the series and the topic I chose was Faith & Gratitude. Some of the other sessions included Faith & Travel, Faith & Science, Faith & Storytelling and even Faith & Spies.

I began by giving this specific definition of what I mean by gratitude – the feeling you experience when you acknowledge having something that’s valuable to you and that came to you as a gift. Whatever it is, you did not get it through any kind of transaction and it’s not anything that you feel is owed to you.

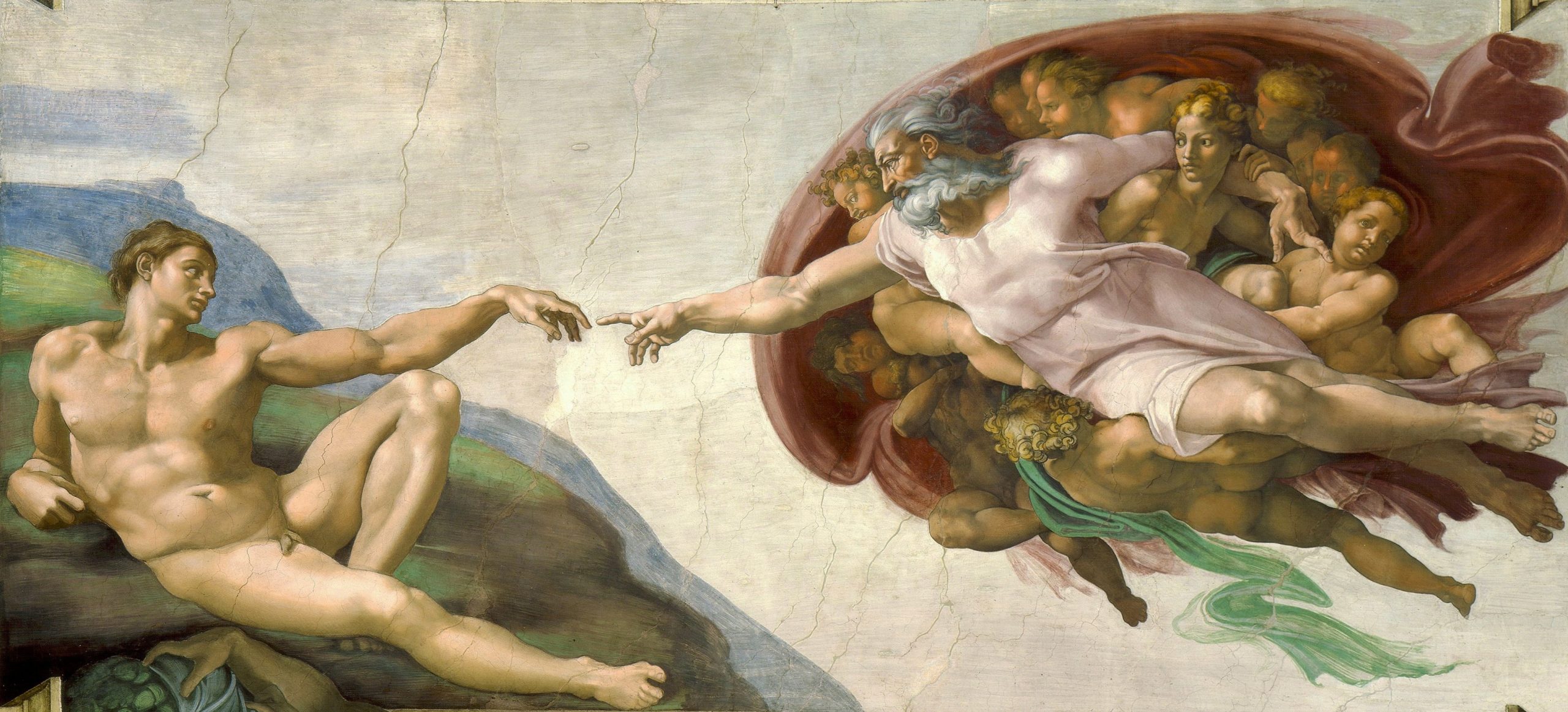

The first slide in my presentation was the image at the top of this post. This is a picture my son took of me on the evening of 8/25/25 on the shore of Lake Anna at sunset. The view was particularly beautiful that evening and if you look closely, you can see the crescent moon that was setting behind the sun. As another person in our group moved closer to the water to get a different view I noticed his silhouette so I quickly gave my phone to my son and asked him to take a picture of me as I struck a pose at the water’s edge. Looking at this picture now I see myself in a posture of gratitude.

10 minutes of my presentation was showing this video, a Ted Talk from 14 years ago by Louie Schwartzberg on gratitude. It is filled with beautiful time lapse photography and is narrated by Brother David Steindl Rast. Here’s a quote from Louie – “Gratitude unlocks the beauty of life. It turns what we have into enough.” and here’s a quote from David – “It’s not happiness that makes us grateful, it’s gratefulness that makes us happy.”

I also took a few minutes to point out the connection between remembering and gratitude. At some point in your life, someone taught you the spiritual disciplines that you practice today. That person may have been a leader, a friend, a grandmother, a pastor, or someone who is no longer with us. We should never forget them and the influence they’ve had on us. In the midst of the pace of work, errands, new friendships, and personal challenges, it can be easy to forget our roots.

Remembering is a form of humility and gratitude. We honor the efforts of those who have invested in our lives when we live with purpose, when we seek to grow, when we share what we learned. Today, think about the person or persons who left an imprint on your spirit. Perhaps it is time to write to them, to pray for them, or simply to give thanks in silence. Their influence is still alive in you, and now you can be that voice for someone else.

P.S. World Gratitude Day will be celebrated on Sunday, 9/21/25

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

There is an ongoing debate in the Christian community about the “sacraments,” or what is essentially necessary to be a Christian. All of our communities agree on two: Communion (Eucharist, the Great Thanksgiving, the Mass) and Holy Baptism. Some traditions (primarily the Roman Catholic) claim you must be baptized in order to partake of the former. My church practices an “open table” theology, which is discouraged by some Episcopal Bishops. In short, the “open table” approach allows anyone to join in the Communion.

This is a sensitive matter for me, since I was “conditionally” baptized on August 19. You see, near the end of her life, my mother admitted to me that I may not have been properly baptized in the Pilgrim Holiness (now Wesleyan) tradition since they frowned on infant baptism. This was startling news because I was confirmed as a Methodist and then an Episcopalian on the basis on what I thought had been my infant baptism. But my mother said I may have just been “dedicated, not baptized.

If you believe all this mumbo jumbo, it’s a big deal. Hence my last-minute conditional baptism, which neither of my parish priests had ever administered. The only difference, is when the priest lays on hands he/she says “if you have not been baptized, then” etc.

It was an emotional moment for me. Adults are very different from infants. They can consider the surroundings, the few parishioners who joined a Tuesday noon mass at my church, the candles, the liturgy, the water on one’s head, the scent of the chrism applied to the forehead.

My rector, the Rev. Fran Gardner-Smith crooked her arm in mine as she presented me to our Assistant Rector. I was very moved. After all, I had served on the vestries of two Episcopal churches and I’m a certified lay Eucharistic minister.

But now I am “properly” baptized. This coming Sunday, we will baptize several Iranian converts. As I recite the baptismal vows, I will rededicate myself to some of the most extraordinary promises that any human can utter. If you are interested, please read What We Believe As Episcopalians, Starting With The Baptismal Covenant

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.