Contributed by Susan Posey, Redeemer Lutheran, McLean

In a world where troubling news abounds, Tysons Interfaith is dedicating 2026 to highlighting “What’s Going Right.” Whether it is individuals, organizations or nations working to improve the lives of others and to build a just and peaceful future for all of us, there is always good news to be found.

We hope the following blog post will bring you encouragement and inspiration to make a positive difference in your own corner of the world.

This week, Ramadan began for our Muslim brothers and sisters, and the season of Lent began for many in the Christian community. As we enter this time of reflection, I hope all (however we experience the Divine) will remember the remarkable journey of the Buddhist monks who recently completed their 2,300 walk for peace.

Their message for individual and collective peace seemed to resonate with people they encountered on the 108-day walk. In deed, people were hungry for it. The ceremony welcoming the monks to National Cathedral on February 10 was attended by thousands of people, including faith leaders from all types of faiths.

In his remarks at National Cathedral, the Venerable Bhikkhu Pannakara concluded that he hopes the message of peace the monks carried is something we will unlock in our own hearts and minds every day.

There are many press accounts about the monks’ incredible journey. Here is just one:

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/buddhist-monks-15-week-walk-peace-ends-washington-dc-rcna258458

To view the ceremony held at National Cathedral on February 10, please visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C5lbugF8PHY

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Rev. Dr. Trish Hall

Have you ever felt totally out of control—like a cartoon character clinging desperately to a wildly spinning object? Or as if you were possessed by some external force, only to discover that the force was actually inside you? At times, emotions can feel like being sucked into a vacuum—one that swirls everything in its path with no regard for what remains standing.

Emotions are powerful. They can cripple or empower. They can paralyze or energize. And during times of upheaval—when what once felt safe and predictable has been overturned—we may forget that we hold within us the capacity to redirect that force. We can transmute emotional chaos into purposeful energy. We can pause, ask, How am I to serve?—and then listen for what wants to emerge through us.

We humans are fascinating creatures. We work relentlessly to make sense of our world, especially when it stops making sense. When life turns upside down, we fight to restore equilibrium—to reestablish a reality where up is up and down is down. We are meaning-making machines, trying to reason our way through the unreasonable.

Often unconsciously, we construct stories that explain why what feels wrong isn’t really wrong—or why it must somehow be justified. We can sustain these narratives for a while. Eventually fatigue sets in. Beneath our explanations we discover fear: fear that life will never return to “normal” (if such a thing ever existed). We grieve the loss of what once anchored us. And for many, anger rises—often directed toward whoever or whatever we believe caused our losses or threatened our sense of safety. Others turn inward, sinking into despair or depression.

This emotional mélange describes the inner world of countless people right now.

Yet there is another remarkable quality woven through our fear, grief, and anger: resilience. It is our survival instinct—the deep intelligence that keeps us moving forward even when certainty dissolves. Emotions themselves are part of that intelligence. They are not flaws in our system; they are the system—internal alerts signaling that something is out of balance, that we no longer feel safe or oriented.

When these alarms sound, our bodies constrict. We feel compelled to defend ourselves and those we love. We cling tightly to the life we once knew, even while doubting whether equilibrium can ever be restored. And yet, paradoxically, it is often in these very moments of instability that our greatest inner strength is revealed. Crisis has a way of calling forth capacities we did not know we possessed.

Many of us were taught to categorize emotions as “good” or “bad.” But emotions are neither. They are intelligent signaling mechanisms—information carriers. What matters is not the emotion itself, but how we interpret and use the information it provides.

Emotional data deserves discernment. Our feelings are filtered through personal history, cultural conditioning, and unconscious bias. Five people can witness the same event and experience five entirely different realities. Likewise, our emotions do not always reflect objective truth. Add to this our innate tendency toward confirmation bias—the inclination to notice what confirms what we already believe while filtering out contradictory evidence. It becomes clear why emotions can feel so convincing in spite of lacking accuracy.

Because we assume something to be true, our emotions react in anticipation of that assumption being fulfilled, reinforcing the belief and strengthening the emotional response. This feedback loop can trap us—unless we pause long enough to examine it.

When we release the habit of labeling emotions as good or bad, a deeper understanding becomes possible. Emotions are energy. And energy can be directed.

Anger, for example, can be paralyzing—or it can be a source of immense strength. We can hand our power over to it, allowing it to rage unchecked, or we can harness its energy to challenge systems that no longer align with our values. The difference lies in conscious choice.

So the real question becomes: Are we willing to remain victims of our emotions, or are we ready to work with them as allies? Are we frustrated enough with being overwhelmed that we are willing to reclaim our power?

Personal transformation is not for the faint of heart. It requires courage, commitment, and a willingness to step into the unknown. Imagine how different life could feel if you were no longer imprisoned by your emotional reactions. Freedom begins when we learn to redirect emotional energy rather than suppress or discharge it.

Fear, grief, and anger each arise from a perceived loss—and each contains an embedded calling.

Fear emerges when the structures we trusted collapse—when our ability to discern what is safe feels shattered, and we believe ourselves powerless against forces beyond our control. Grief surfaces when the loss feels final—when hope dims and helplessness deepens isolation. Anger arises as a demand for change, an eruption of pent-up energy seeking movement and expression. Frustration often speaks through anger, which—when channeled consciously—can be profoundly constructive.

To uncover the wisdom within these emotions, we must ask a different question: What would I rather experience? This shift in perspective opens a powerful truth—we already possess what we need to change direction. While we cannot control how others respond or whether the world conforms to our desires, one thing is absolute: when we change, our world reorganizes around that change.

This realization is profound. When we declare “enough is enough” and draw upon our inner strength, we discover that we are not broken—we are latent potential waiting to be activated. As Mother Teresa reminded us, “Not all of us can do great things. But we can do small things with great love.”

Within fear lies the desire to rebuild trust and restore connection. It calls us toward community, collaboration, and service—toward groups that identify needs and work together to meet them.

Within grief lives empathy—the capacity to sense what others are enduring. It invites us to nurture, to accompany, to bring tenderness where there has been harm.

Within anger resides the energy for change. Mobilized anger becomes action: marches, advocacy, prayer circles, meditation gatherings, visible stands for justice and healing. Mobilization simply means movement—transforming frozen rage into purposeful engagement. Healthy anger requires healthy outlets.

Each of these emotions carries transformative potential. Grief can deepen compassion and meaning, allowing sorrow to be felt without drowning in it. Fear can sharpen discernment, draw us into presence, and cultivate trust rooted in clarity rather than denial. Anger can bring focus, agency, and healthy boundaries, helping us identify what must be protected or changed.

The invitation is ours: to choose conscious outlets and step into action.

One way to begin is through reflection. Recall people or situations that have brought out your truest self. Who were they? How did they show up? What about them called to you? These attractions are not accidents. They signal alignment. Something within you recognizes something possible.

Allow images of work, service, or volunteer opportunities that embody these qualities to surface. Compare their attributes with what brings you joy. Then invite the emotional energy that once held you captive to fuel engagement—especially in forms of service that involve giving of yourself.

Research consistently affirms what many of us intuitively know: when we give from the heart, we receive profound benefits. Volunteering is associated with reduced anxiety and depression, increased life satisfaction, greater emotional resilience, enhanced social well-being, and improved overall quality of life. Emerging research even suggests links between consistent community engagement and slower cognitive aging.

Perhaps most importantly, service shifts our orientation from self-absorption to being a beneficial presence.

Our emotions are not obstacles to overcome. They are invitations. When we listen deeply, redirect wisely, and act courageously, fear, grief, and anger become pathways—not prisons—guiding us into lives of meaning, connection, and purpose.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Yerusalem Work

Like so many people, I seek to please God (Allah). In Arabic, the name Allah is held highest. It has no gender or plural form. When becoming Muslim, reverts study Arabic, which often inspires and enlightens, humbles and challenges. It is incumbent upon Muslims to learn Arabic well enough to pray or make salat, which is formal worship. The journey to Islam is paved with wisdom and guidance. Allah guides and makes the Straight Path known to believers.

For so long in the interfaith community, I have tried on different head coverings (some say, hats) as an adherent of a faith or in solidarity with a people. Muslim women are taught to wear a veil as an expression of faith and modesty through a Quranic injunction (Surah An-Nur (24:31) & Surah Al-Ahzab (33:59)) that describes a Muslim woman’s responsibility to embrace hijab. Christian women are obligated to wear headscarves when praying or prophesying according to Paul, the author of the First Epistle to the Corinthians in the New Testament. Orthodox Jewish women often wear head coverings once married. There is value in wearing a head scarf whether modesty or subservience.

Muslim men and Jewish men have an opportunity to wear head coverings (a kufi or taqiyah for Muslim men) (a kippah for Jewish men). Outside Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, head coverings are implemented to reflect spirituality, for example, in the Sikh traditions.

As we near February 1, 2026, World Hijab Day, it is important we exercise our sacred right to express our faith and our right to choose how we present ourselves in public or private. In the United States, there is no ban on the hijab per se, but a significant percentage of employers discriminate against women who wear hijab, though it is against the law to act on such prejudice. On one end of the spectrum, some people oppose Islamic practices, altogether. This level of hatred and bigotry may even extend to other marginalized groups of religious congregants, however diverse. On the other end of the spectrum, there are people who flourish in their distinctive, cultural, and religious traditions.

It is our right to wear hijab. Here in this brief video, we hear “The Miranda Rights for Hijabis” This is an excerpt from my poetry collection, “Watery Eyes: Reflections of a Muslim Woman” It combines humor, purpose, and power.

According to U.S. law, citizens when arrested have the constitutional right to remain silent and the right to an attorney. For so many of us, our hijabs speak for us and we have no one but Allah (swt) to protect us. So, I devised this version of the Miranda Rights for Hijabis (women who wear hijab).

You have the right to wear hijab. Anything you say or do will be used to prove your Islam. You have the right to stand before Allah on the Day of Judgment. If you cannot afford a copy of the Quran, one will be provided for you. Do you understand the final revelation of Allah (SWT) given to the Prophet Muhammad, (SAWS), is a mercy for all mankind? With your faith on the line, do you realize the entire earth is a masjid, a place for prayer and purification? Will you pray as Muhammad, (SAWS), prayed?

#UnityInHijab

Your hijab may be a form of dawah (an invitation). You may invite others to Islam through sparking a conversation about faith or developing a friendship as a result of authentic expression.

On World Hijab Day, February 1st, women all over the world can celebrate the opportunity to wear a veil whether for the purpose of modesty or inclusion, solidarity or spiritual union. Hijab is not a sign of oppression; it is the evidence of a powerful form of self-expression whether the collective self or individual self. It gives us freedom from distraction in everyday conversation. It centers our day around Allah (swt), making it easier to submit our prayers.

Wearing hijab, a head covering, leads to a paradox. It makes us standout, not just for who we are, but what we believe. It makes us a representative of the One Who is unseen. This combination of visibility and invisibility empowers women who are meaning-driven. We find purpose in wearing hijab—if for no other reason than to please Allah (swt).

SWT in Arabic stands for “Subhanahu wa ta’ala” (سبحانه وتعالى), meaning “Glory be to Him, the Exalted,” or “Glorified and Exalted is He,” a phrase used by Muslims to show reverence and praise when mentioning Allah (God).

SAWS In Arabic, “SAWS” is an abbreviation for “Sallallahu Alayhi Wa Sallam” (صَلَّى اللّٰهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ), meaning “Peace and blessings of Allah be upon him,” a phrase used by Muslims out of reverence and respect after mentioning the name of the Prophet Muhammad.

Yerusalem Work, a creative writer with a heart for interfaith dialogue, is an educator, passionate about community building. A holder of a master’s degree in library science and a prolific author, she regularly blogs and self-publishes her writing. Her writing has been published in Muslim Matters, Islamic Horizons, and Tysons Interfaith. She considers it an honor and a pleasure to write on Islamic themes.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal

I went to Eckerd College (the name changed from Florida Presbyterian College my freshman year)

which considered itself a peer and competitor to New College, the small liberal arts college

completely remodeled by Florida’s conservative governor. nytimes.com/2025/12/28/us/new-college-ron-desantis-florida-conservative

Eckerd had a “core” curriculum – one required class every semester, January independent study

excepted (FPC invented the 4-1-4 calendar), which like New College’s program was completely up

to the student. My freshman year, for example, a dorm mate built a harpsichord while I read Horace,

Juvenal, and every book written by Kurt Vonnegut and wrote a paper on the latter while nursing a

broken ankle (from basketball). The first year “core” syllabus included Homer’s The Odyssey, which

every student at New College is now required to “read” during one excruciating seven-week course.

I like Eckerd’s or FPC’s approach better because our semester-long class included quaint items like

The Bible, and authors like Alfred the Great, Rabelais, Milton Friedman, Arthur Koestler, etc.

As I read the Times article, I remembered the debate that raged on campus during my freshman

year: students opposed plans to eliminate the Classics department because few if any of our 1,000

students wanted to study it. Even our tiny Asian Studies program and Chinese language class, very

rare in 1972, was larger. I can’t remember what they decided to do, but the school, like New

College, fell on hard times after the name change (students went insane and strutted around

campus wearing “Eckerd Drugs College” tee shirts made overnight by the arts students) and the

fraudulent mismanagement of their small endowment fund. Like New College, Eckerd had to be

taken over by the state and is now much larger school that still features on lists of colleges that

“change people’s lives.”

I’m not sure how to react to the quotation from a New College student recruited to their new beach

volleyball team, “wooed with scholarships, to play on sand that is fluffed twice a week, with a view

of students kayaking on the bay.” She said she “was raised in a ‘very old school family,’ and

educated in Christian private schools but sees no ideological divisions on campus: ‘I think

everybody minds their own business, does their own thing.’”

Now that seems like a positive development, but sometimes my faith tells me we need to stop

minding our own business and get involved. Happy New Year.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the

views of Tysons Interfaith or its members

And Why Their Name No Longer Captures Their Scope

In a world where troubling news abounds, Tysons Interfaith is dedicating 2026 to highlighting “What’s Going Right.” Whether it is individuals, organizations or nations working to improve the lives of others and to build a just and peaceful future for all of us, there is always good news to be found.

We hope the following blog post will bring you encouragement and inspiration to make a positive difference in your own corner of the world.

Contributed by Michael Goldberg, The Baha’i Community (Written with help for AI)

When the Abraham Accords were signed in 2020, their headline seemed simple: diplomatic normalization between Israel and a few Arab states. But as the geopolitical landscape evolves, that label – “Arab–Israeli” – no longer captures what the Accords have become. According to a recent op-ed in the Jerusalem Times titled “Abraham Accords are no longer Arab-Israeli accords”, the framework has outgrown its original identity: it’s evolving into a new paradigm of regional cooperation that extends far beyond the traditional Arab–Israel divide.

At its heart, the Accords were always meant to be more than a bilateral ceasefire or a one-off diplomatic gesture. They were envisioned as the foundation for a shared future built on diplomacy, commerce, security, and cultural exchange. In just five years, that vision has expanded in ways few predicted – turning the Accords into a “blueprint for a new world order,” one where former divisions fade and constructive collaboration becomes the norm.

A striking example of this expanded scope is the recent inclusion of Kazakhstan in 2025 – the first non-Arab, non-Middle Eastern country to formally join. With that accession, the “Arab–Israeli” formula simply no longer applies. The Accords are becoming a broader “coalition of cooperation,” increasingly defined by shared interests rather than shared ethnic or cultural identity. As some commentators put it: the Accords are now a platform where nations define themselves not by who they fight, but by what they build together.

It’s a transformation with both symbolic and strategic weight. Symbolically, it signals that Middle East peace and cooperation no longer depend solely on historic alliances or regional identities – but on common values and common goals: security, development, and integration. Strategically, it expands the potential membership of the Accords far beyond the Arab world: any country that values regional stability, trade partnerships, and diplomatic openness could become part of this emerging network.

That said, the road ahead is anything but smooth. The Accords have survived war, regional upheaval, and deep political tensions. But their future – and the future of any expanded coalition – depends on whether participating countries remain committed to diplomacy over polarization. The ongoing war in Gaza, for instance, has tested many of these relationships and has shaken public sentiment across the region.

Still, none of the signatory states has withdrawn. The basic architecture remains intact. Economic cooperation, security coordination, and diplomatic channels continue – though momentum has slowed. Moreover, some analysts believe that once conflict subsides – and once a credible diplomatic roadmap for the larger region re-emerges – the Accords’ expansion could resume.

In that sense, the renaming (or re-conception) of the Accords is more than semantic — it reflects a tectonic shift. It suggests that peace and partnership in the 21st century Middle East (and beyond) are less about historic divisions and more about pragmatic cooperation. The Accords are no longer simply an “Arab–Israeli” phenomenon: they are a budding multilateral alliance, one defined by shared purpose and mutual benefit.

Whether they will endure – and whether more countries will join – remains uncertain. But as the article argues, their evolution offers a path forward: one in which identity gives way to interdependence, fear gives way to collaboration, and old paradigms give way to new possibilities.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Susan Posey, Redeemer Lutheran, McLean

A local volunteer group, Fairfax Tree Rescuers, has launched an initiative called the Fairfax Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management (PRISM). They will be holding a number of removal events throughout Fairfax County the week of November 8 through 16, 2025.

Volunteers are asked to register for the events and to wear long sleeves, closed toe shoes and insect repellant. Tools from home, such as loppers, clippers and pruning saws are welcome, but no power tools, please. For a complete list of the PRISM events this week and to register, please visit: www.fairfaxprism.org/upcoming-events. You can also sign up for their newsletter.

The Fairfax County Park Authority also has a volunteer program for invasive plant removal on its properties. You can learn more about the program at www.fairfaxcounty.gov/parks/invasive-management-area.

Care for the environment is just one of the values held in common by the faith traditions of Tysons Interfaith. To learn more about Tysons Interfaith and about local interfaith events, please consider signing up for our monthly newsletter at LINK.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

I am a long-time and proud member of WPFW, “Jazz and Justice Radio,” a wholly community-owned station in D.C. While I do not agree with their extreme progressive views on justice, I appreciate wholeheartedly their jazz programming, the last vestige of a proud Washington tradition that dates from the days of Duke Ellington or even earlier.

One thing I like is they take no money from anyone – corporate or government sponsors – and all their DJs are volunteers. The paid staff are the technicians who keep the records spinning, the transmitter working, and the lights on.

WPFW’s overnight and early morning programs are particularly good though there are probably few people listening. Every day is different, but Thursday a.m. is one of my favorites. Here’s the playlist from Papa Wabe’s “Free Your Mind” show this morning.

| 04:04 AM | Everton Blender | Slavery Ship | Slavery Ship | Blendem Production |

| 04:08 AM | Admiral Tibet | Victim Of Babylon | Victim Of Babylon | VP Records P&D |

| 04:12 AM | Bunny Wailer | Rise and Shine | Liberation | shanachie |

| 04:20 AM | Lila Iké | Scatter | Treasure Self Love | Ineffable Records |

| 04:34 AM | Monkixx | Stone Me (Original Mix) | Year One Compilation | Unified Audio |

| 04:36 AM | Alberto Tarin | You Go to Elder’s | Jazz’n Reggae Showcase Vol. 1 | Brixton Records |

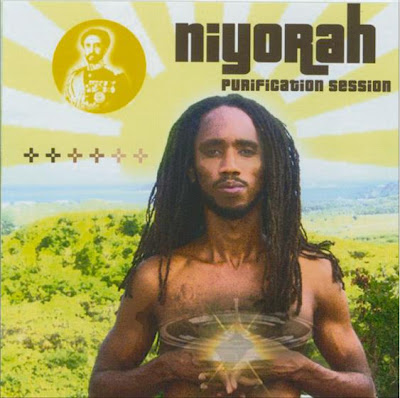

| 04:39 AM | Niyorah | We are the One | Purification Session | I Grade Records |

| 04:47 AM | The Wailers | Stand Firm Inna Babylon | One World | Sony Music Latin |

| 04:55 AM | Luciano featuring Louie Culture and Terror Fabulous | In This Thing Together | Fatis Presents Xterminator ft Luciano & Friends | Xterminator Productions Ltd. |

| 04:59 AM | Bryant Sarmiento | September (Instrumental) | September (Instrumental) | Bryant Sarmiento Productions |

You will have a hard time finding these “songs” – a couple are really sermons — and I’m certainly not an expert on reggae or Rastafarianism, but before we were married my wife used to live one floor down from a group of Rastafarians in Brooklyn, N.Y. Smoke is supposed to rise, but let’s just say we were often wafted by more than the thumping bass of their speakers.

What Papa Wabe has done here is truly outstanding. Here is my favorite from Niyorah. Sorry, lyrics unavailable: Spotify Link

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Rev. Dr. Trish Hall

At Centers for Spiritual Living, our core belief is Oneness – the inseparability of all creation.

“We believe in God, the Living Spirit Almighty; One indestructible, absolute, and self-existent Cause. This One manifests Itself in and through all creation but is not absorbed by Its creation. The manifest universe is the body of God …”

All Creation is the result of the Creator expressing Itself in form. Its activity is Love. Within the One we are inseparable from one another – those we love and like and those we don’t like and yet are called to love.

We believe our world is the manifestation of God. There is nothing else so the Allness of God includes everything. Everything is within this One Creation. Within this creation are people and things we love and try to understand, and people and things that we find incomprehensible. It includes people we do not like and those we deem to be unlikable.

The task of loving those we have labeled unlikable varies from relatively insignificant to paralyzingly daunting. Our world view tends to dictate how we relate to all people – the likables and the detestables. Our emotional responses may vary from casually acknowledging that some people do not appeal to us or hold views that are incompatible with ours, to finding ourselves triggered having gut-level reactions and fear. The call to love our neighbors isn’t subject to our emotional responses. The call is clear and is not to be ignored.

Before looking at loving “the unlikable” we need to consider “unlikability.” How is it determined and by whom? The dictionary tells us that unlikable is detestable, despicable, contemptible, worthless. I ask based on what criteria? I invite you to contemplate the difference between UN-likable, which seems to focus on the nature of the person, versus DIS-likable which seems to relate more to the temporariness of behaviors. So far, I have not met a parent who hasn’t shared that there have been times when they really didn’t like their offspring yet never wavered in their love for that child. They didn’t declare that child unlikable, they disliked the behavior and loved their kid. Dislikable then seems to be redeemable, whereas someone deemed unlikable is inherently flawed.

Likeability is subjective. It is an opinion formed by an individual that then is spread to that person’s circle and ripples out coalescing the perceptions of greater numbers of people. Interestingly, the process works whether positive or negative. It is used by celebrities of all kinds. The process is impartial. History is fraught with examples of how the same process has been used destructively. Instead of uplifting someone or moving some great cause forward, it has been used in the opposite direction to impose misery and injustice. The process can engender mob mentality. All it takes is someone deciding something about someone and spreading their opinion about that person (aka gossiping), stirring up mobs of like-minded people into acts of violence. You may say those are extreme examples, and I will challenge that the pattern that conducted witch hunts in the 15th to 18th centuries, is as alive and well today as it was then. It was a demonstration of raging prejudice then. It remains a demonstration of raging prejudice now. The focuses of the prejudgments may have changed; the resulting behaviors have not.

How is unlikableness determined? By whom? On what criteria? Is there an unlikableness scale? Where do you get the information on which you have formed your opinions?

I invite you to examine your own beliefs – to challenge them – to form your own opinions whether or not they are compatible with your family and friends.

Let’s start fresh. Let’s begin by honoring what we are and why we have the ability to decide what is right for us personally. As Jane Goodall said, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” It is your right to choose to not examine your beliefs, to conform to some external expectations and remain as you have been. And you have the right and the privilege to decide to change radically or anywhere in between. We are blessed that we have those options. We have those choices because we are endogenous beings – our origin is internal rather than dependent upon external forces. We are thinking beings that have the power to choose our own courses of action. I believe that exercising that privilege is our responsibility.

As believers in Oneness, is there a space for anyone to be judged unlikable? Perhaps, very dislikable?

Preparing for this self-examination, a first step might be to look closely at our own criteria. Is it a reflection of the society in which we live or our personal values? Have you reviewed the input of others (media, relatives, etc.) to determine whether it is in alignment with your values – with how Spirit within you is calling you to be?

Oneness assumes that everyone and everything is the expression of One Creator. Different traditions have given this one creator myriad names. The names can limit our perceptions – our assumptions about it. They cannot limit the Creator. Oneness asks us to accept that it includes what we understand and what we don’t, what we like and what we don’t, what we love and what we don’t. Oneness calls us to be so open that we can be in the midst of apparent disparities and contrasts and learn strategies to live in peace celebrating diversity within the Oneness. Oneness invites us to be in integrity and live into the change we want to experience. Some tough questions remain: Are our hearts big enough to hold a space for those whose behaviors appall us without judging them to be inherently (perhaps permanently) flawed? Can we expand our concepts of being present with those we do not understand so that we can learn from them while remaining grounded in Love? Are we willing to be open to the possibility that we can create a world that works for all especially when it requires collaboration with the dislikables? Are we bold enough to be peace makers in the midst of the antithesis of peace?

Jane Goodall declared, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” I ask, Do you have the courage to stand as Oneness, as a Peace Builder … to be a change-maker?

To learn about the Centers for Spiritual Living’s Global Heart of Peace Initiative, please visit: https://csl.org/spiritual-community/heart-of-peace/.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Stephen Wickman, St. Thomas Episcopal, McLean

“Why Have Empathy for Those Who Never Extend It?” is how Qasim Rashid begins a brave essay that reflects on the death of Charlie Kirk Reflections on the Death of Charlie Kirk. It is well worth the time to read his thoughts in full, but here is a summary:

Rashid argues that Kirk rarely extended empathy and often poured contempt on many groups of Americans, including Muslims, engendering hatred.

And he returns to a verse from the Qur’an for guidance:

“O ye who believe! be steadfast in the cause of God, bearing witness in equity; and let not a people’s enmity incite you to act otherwise than with justice. Be always just, that is nearer to righteousness. And fear God. Surely, God is aware of what you do.” — Chapter 5, Verse 9

Rashid detests and works ferociously to counter what he views as the hatred that Kirk engendered but at the same time does not allow these injustices to make him retaliate in kind. As he puts it: “I will not allow his fear of the other infect my ability to see the humanity in every person.”

And here is an important comment from the niece of Rev. Martin Luther King:

‘And now while his family and this nation grieve, some are calling him a racist. A white supremacist. Even a fake Christian. Such accusations are conversations unbecoming to a Christian,” she continued. “In the final analysis, Charlie stood for life, for faith, and biblical truth. He wasn’t afraid to say the name of Jesus in the public square, and he paid a price for it. Now is not the time to attack Charlie. It’s the time to lift up the banner of Christ as the member of the one blood human race Charlie Kirk did. His legacy of public discourse of bringing difficult conversations to the table mattered. He caused us to think and to pray. Charlie has gone to meet his maker. May he rest in peace. May we honor him today by praying for his family and by answering this question: Where will you spend eternity?’

“Such empathy or hard “love” is a basic premise of all our faith traditions. I disagree with Kirk on most things, but especially on his treatment of the LGBTQ community, Muslims and “progressives,” but like Rashid’s, my faith requires me to respond with kindness even as I express my disagreement.

In the Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church, there is a prayer for one’s “enemies” that carefully balances responsibility on both sides of a conflict:

“O God, the Father of all, whose Son commanded us to love

our enemies: Lead them and us from prejudice to truth:

deliver them and us from hatred, cruelty, and revenge; and in

your good time enable us all to stand reconciled before you,

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

In that spirit and in the spirit of Islam and other faith traditions, let us extend our empathy and love, without prejudice, to the Kirk family and his supporters.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.

Contributed by Susan Posey, Redeemer Lutheran Church, McLean

A friend of mine recently shared a link to an article published in Time entitled, We All Deserve Dignity and Respect. It is authored by Russell Nelson, the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints on the occasion of his 101st birthday! Mr. Nelson’s observations are his gift to us, and I for one, found them to be very encouraging.

Here are a few snippets:

“The world has changed dramatically. Yet what I have learned is that some truths do not change. These enduring truths are what anchor us in turbulent times.”

On the occasion of my 101st birthday, I wish to share two such truths – lessons that I believe contribute to lasting happiness and peace.

First: Each of us has inherent worth and dignity. I believe we are all children of a loving Heavenly Father. But no matter your religion or spirituality, recognizing the underlying truth beneath this belief that we all deserve dignity is liberating – it brings emotional, mental, and spiritual equilibrium – and the more you embrace it, the more your anxiety and fear about the future will decrease.

Second: Love your neighbor and treat them with compassion and respect. A century of experience has taught me this certainty: anger never persuades, hostility never heals, and contention never leads to lasting solutions.”

Regardless of your religious or spiritual practice, I think there is much wonderful food for thought in this article, the full text of which can be found here.

Happy Birthday, Mr. Nelson, and thank you for sharing your wisdom with us.

This blog post is the expressed opinion of its writer and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tysons Interfaith or its members.